I figure lots of predictions is best. People will forget the ones I get wrong and marvel over the rest.

—Alan CoxThe best qualification of a prophet is to have a good memory.

—Marquis of Halifax

I must be off of my rocker to try and make sense of profoundly mixed economic data and provide economic forecasts immediately preceding a presidential election, especially this particular three-ring political circus. However, before you have me committed to Bedlam, please note that I strongly considered delaying this memo until after November 3rd, when we will all know who will control the Executive and Legislative branches of our federal government, and therefore be better able to predict what may be forthcoming as a result. I could have very easily blamed the delay on the hours I spent trying to get through this election’s War and Peace-sized California Voter’s Guide. Seriously, 112 pages? However, perhaps against my better judgment, I have decided just to get on with it. Time is money, after all.

In short, November’s election will likely and very consequentially impact future economic, fiscal, and tax policy. While I generally avoid political discussions here – Lord knows that we get plenty of that elsewhere and I care not to offend (any more than usual, anyhow) – the significance of this election cannot be overstated, if seen only through a fiscal and economic lens. COVID-19 is still wreaking havoc on the global economy, disrupting nearly every facet of life. Ten states reported their highest level of new cases just this past Friday. With the timing, availability, and efficacy of a vaccine unclear, when and how the economy and our way of life return to “normal” remain uncertain. While the economy will recover, the pandemic will leave deep scars, creating difficult policy choices and trade-offs no matter who emerges victorious in November.

Should Biden prevail and the Democrats take control of Congress, we should – at a minimum – expect impactful tax reform, reversing much of the Tax Jobs Creation Act of 2017 and substantially increasing taxes on wealthy individuals, estates, and corporations. I anticipate that some very favorable commercial real estate related tax laws (e.g., 1031 transactions, bonus depreciation, reduced taxes on real estate related LLCs) will go the way of the dodo bird. Additional and significant economic stimulus (read: trillions) will arrive, with aid directed to families, schools, restaurants and small businesses, airline workers, and those blue-collar workers particularly impacted by COVID-19. Government borrowings and our deficit will grow substantially, at least initially, expanding upon 2020’s already daunting $3.1 trillion budget deficit.

Should Trump prevail and Congress remain divided, the next four years will experience continued legislative gridlock, with the courts and judges playing an increasingly outsized role in interpreting, if not implementing, policy. Additional economic stimulus will be delayed and may never arrive. Late-night comedians, political pundits, former White House staffers turned book writers, and cable news personalities will continue to thrive. Much else is harder to predict, if just because political and other divisions will fester and likely produce unpredictable outcomes.

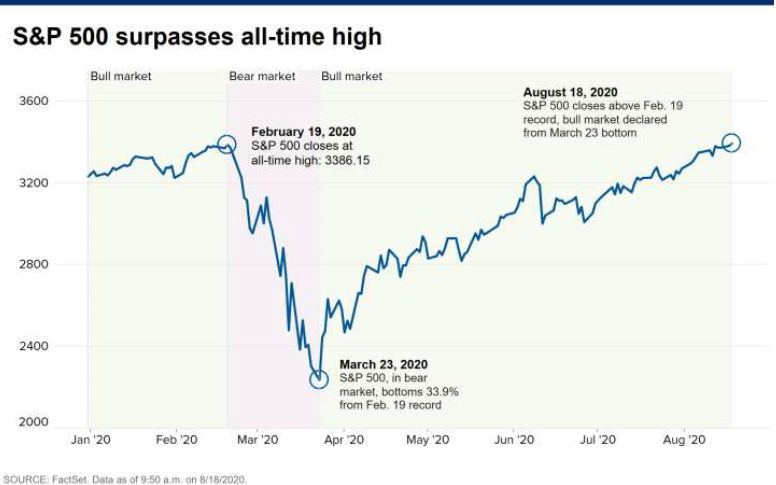

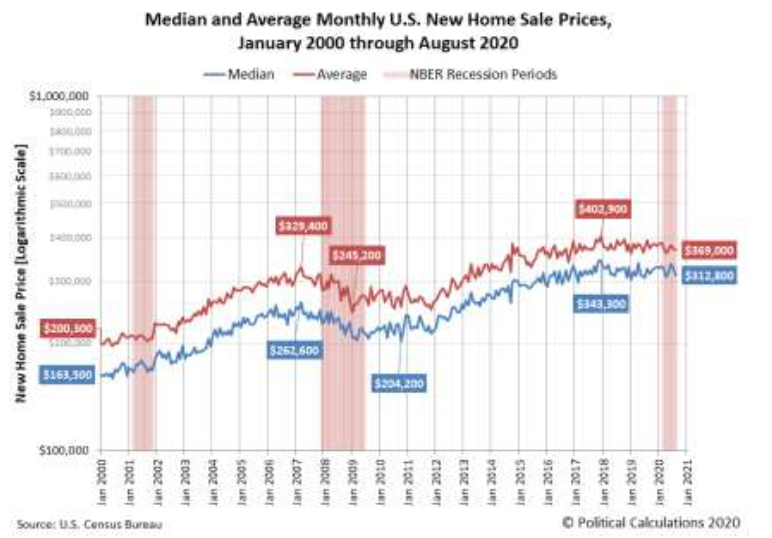

With this being said, it is not surprising that this has been the most uneven economic recovery in modern U.S. history, which some have aptly described as a “K”. White-collar workers and those owning financial assets are faring well enough, while the working class and those owning few financial assets, struggle. Consider that Wall Street experienced its best back-to-back quarters since 2009, with the S&P 500, DJIA, and NASDAQ up 8.5%, 7.6% and 11%, respectively, during just the third quarter alone. Domestic equity markets are up more than 50% since spring, with indices trading at or near all-time highs on both an absolute and relative (price-earnings ratio) basis. The median home price (asking) in the U.S. climbed to $350,000 in September, up over 11% from the prior year, according to realtor.com, an all-time record. Again, those who own equities and real estate are relatively happy campers.

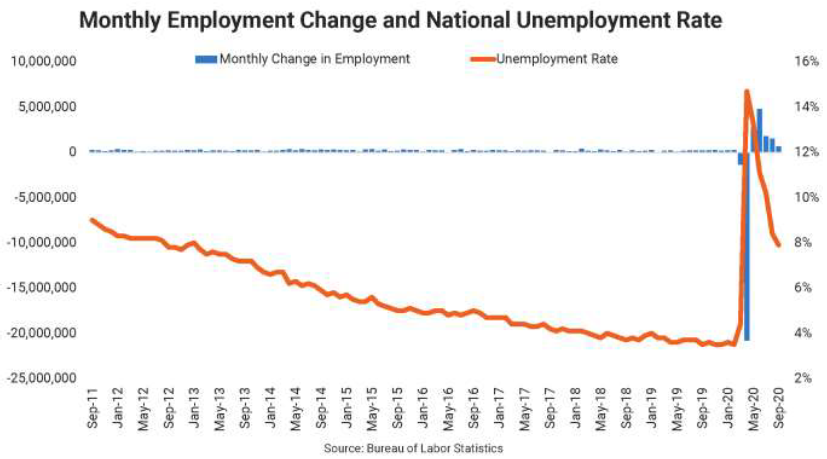

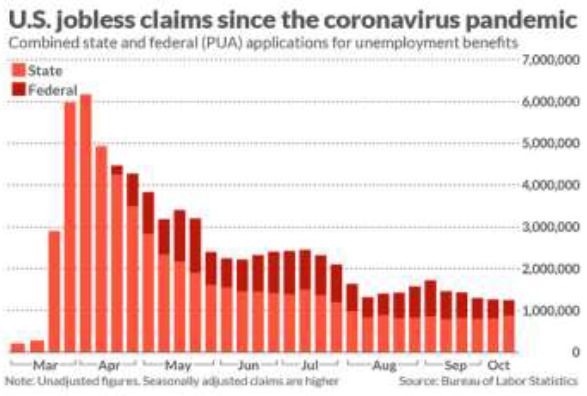

Meanwhile, the labor market has stagnated, with the national unemployment rate sitting at 7.9%. While perhaps a noteworthy improvement from the double-digit unemployment rates experienced earlier this year, unemployment has more than doubled from pre-pandemic levels, and there are gloomy clouds on the horizon. Jobless claims have jumped yet again, with first-time claims for the week ending October 15th, hitting their highest levels since August (898,000), while some 700,000 workers have left the workforce. In addition, a number of large companies have recently announced new rounds of layoffs: Disney (28,000 across its U.S. theme park division), Royal Dutch Shell (9,000), and Boeing and several of the major U.S. airlines (as many as 100,000, collectively). The National Restaurant Association said that some 100,000 restaurants have closed over the past six months, putting three million employees out of work. Again, it is a tale of at least two economies, for those that have, and those that do not.

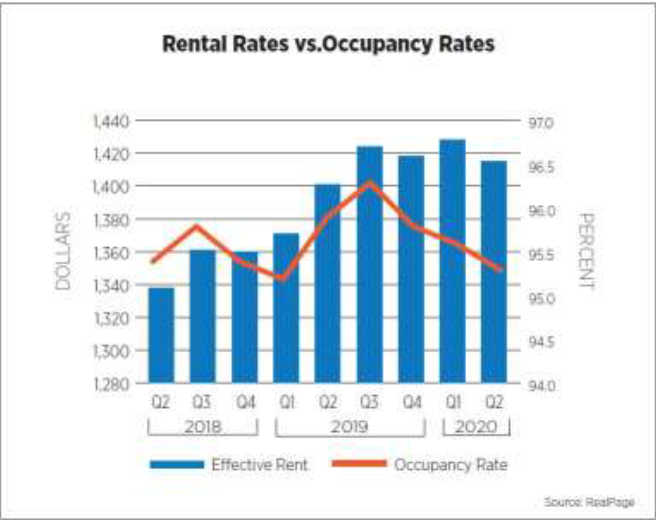

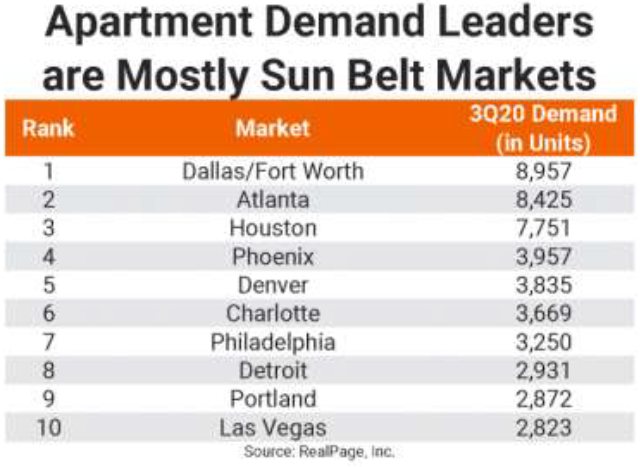

In this economic dichotomy, the multifamily market continues to perform fairly well, though headwinds and tailwinds are engaged in a fierce tug-of-war, providing mixed results. Overall, physical occupancy remains high, over 95.0% nationally, though rents have softened. Occupied apartments climbed by nearly 147,000 units in the third quarter, nearly four times second quarter figures. While over 90% of apartment households paid full or partial rent in September, these results reflect declines (about two percent) from the prior year, and in the absence of further government largesse and marked improvement in the job market and unemployment claims, I see more downside to these results, especially in certain markets.

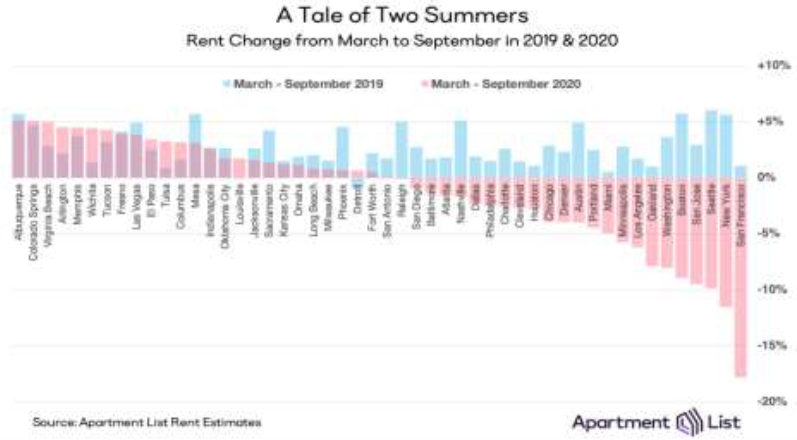

However, as I have discussed previously, different market segments and geographies are witnessing different results. For example, New York and San Francisco have experienced double-digit percentage rent declines over just the past six months. I recently read that there are some 16,000 empty apartments in New York City, the highest level since the 1970’s, nearly tripling the vacancy rate. Meanwhile, other markets (e.g., Albuquerque, Colorado Springs) are achieving rental growth, albeit modest, and attracting residents from more expensive (read: California) locales. It is not surprising that it is these markets – principally in the Sunbelt – where Clear Capital is focusing its acquisition and underwriting resources. Our recent offerings in Lakewood, Colorado, and Carrollton, Texas reflect our views and perspective. Even with our principal focus on the Sunbelt, our primary focus is always on the upside of real estate. As such, we are seeking opportunities in the Golden State that we call home. While this is somewhat of a contrarian approach, we believe there are good opportunities in California – mainly in the Inland Empire region and in workforce housing assets.

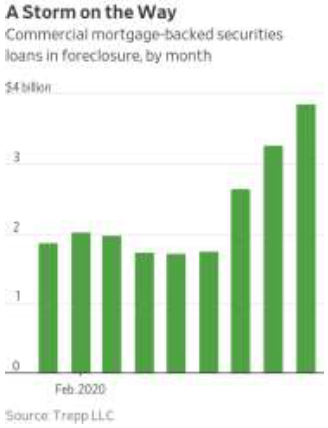

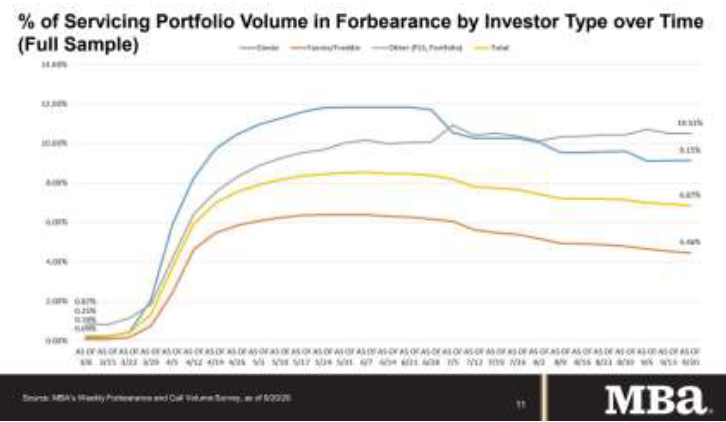

In summary, I don’t anticipate the economy and employment to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2022, with a double-dip recession quite possible between now and the end of the first quarter of 2021. However, much depends on the upcoming election and what government stimulus programs arrive…or not, and whether lenders continue to work with borrowers and forbear delinquencies to prevent a wave of foreclosures and forced sales. Presently, some 3.5 million home loans (about 7.0%) were in forbearance as of September 22nd, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association, and commercial foreclosures have been creeping upwards.

Low interest rates and substantial liquidity will continue to provide critical foundational support to markets and asset values, and while we continue to believe strongly in the multifamily story, conservative underwriting and sensitivity analyses are a must.

While apartment fundamentals remain intact, transaction volumes have dropped sharply, and bid-ask spreads, have widened. Meanwhile, the single-family residential market has surged in the face of record-low supply and interest rates

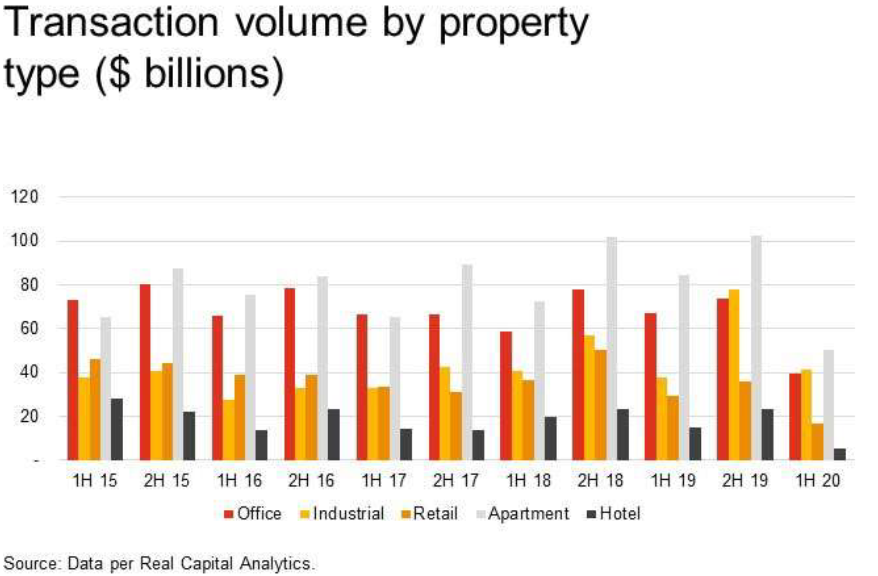

Commercial real estate transaction sales volume (including apartments) dropped by two-thirds in the second quarter from the same period last year, and while data for the third quarter has yet to be released, I anticipate that it will reflect similar declines. According to CoStar, some $35.5 billion in transactions closed in the second quarter, down 69% from the nearly $114 billion in sales during the same period last year. Meanwhile, property listings dropped 15%.

Yet, apartments are still attracting significant investment capital. In one noteworthy transaction, CIM Group, a local institutional player here in Southern California, purchased a 2,346 unit portfolio in Alexandria, Virginia, for over $500 million. Closer to home, Clear Capital listed one of its assets for sale in the third quarter, an affordable project in Azusa, California (Iris Gardens), and attracted multiple bidders. Reduced rent headwinds are being offset by lower interest rates, liquidity, and certain demand tailwinds.

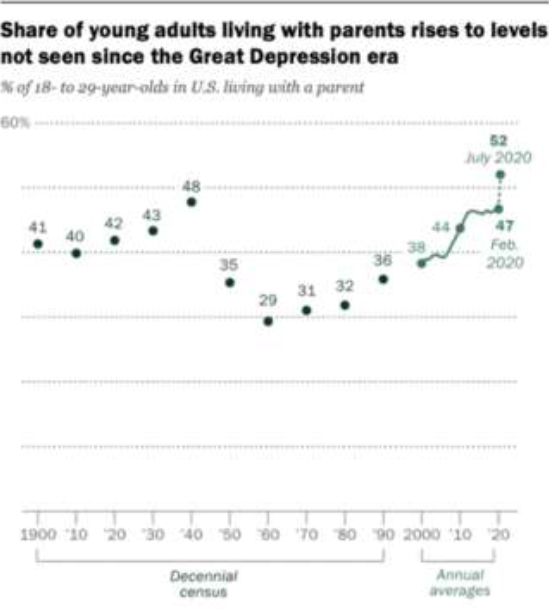

However, the pandemic has certainly shifted what renters seek in units. One is space. Prospective tenants want larger units and common areas. Bachelor, single, and studio units are not nearly as popular in the era of COVID as larger two- and three-bedroom units, and with good reason. Previously, tenants placed great value on swimming pools, gyms, and flexible common areas. Now, with so many residents working from and eating at home, balconies, package lockers, and HVAC/air filtration systems have become relatively more appealing. Record numbers of young adults (18-29) have returned to the nest as a result of COVID, university closures, and stubbornly high rents. Ultimately, these youngins will return to the rental market, so when the economy more sustainably recovers, these prospective renters should provide additional tailwind to the multifamily market.

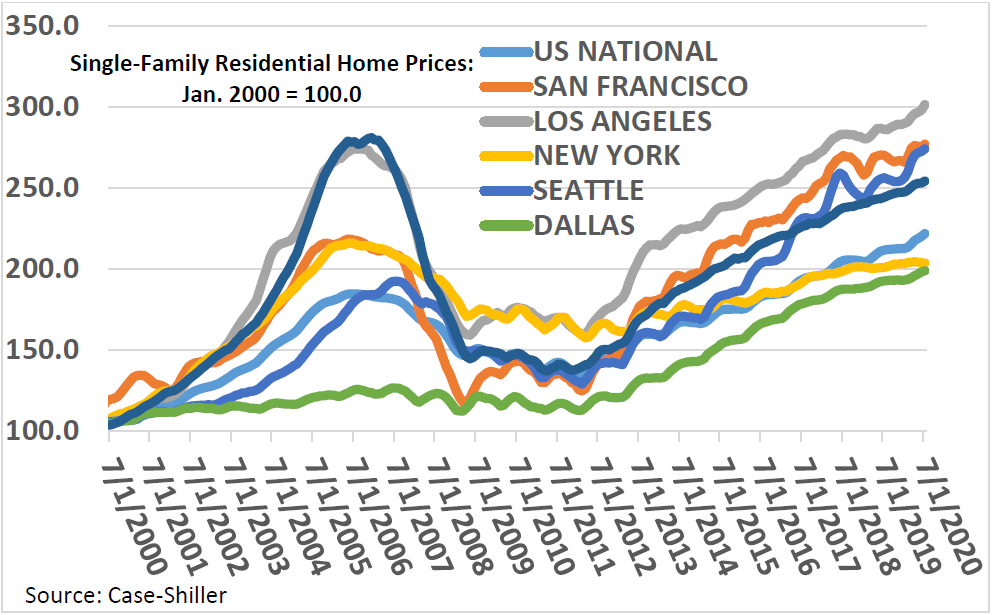

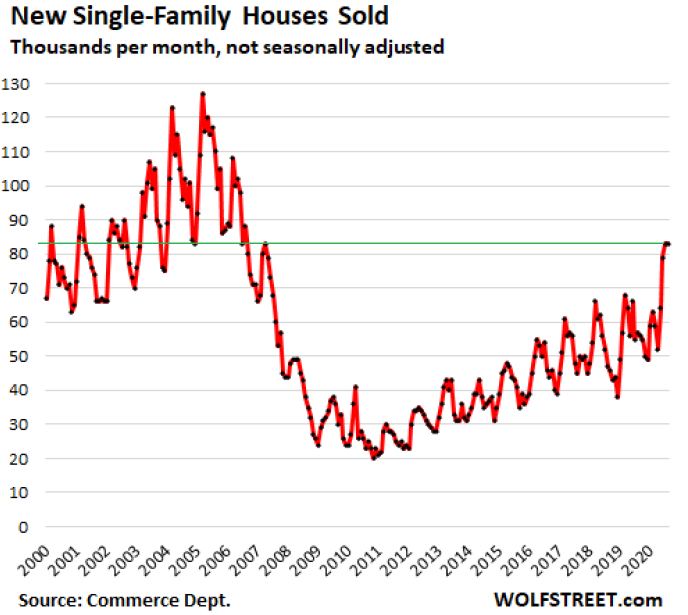

Meantime, the single-family residential market continues to shine, reflecting pent-up demand, relocations to the suburbs from urban cores, record-low numbers of homes for sale, a dearth of new construction, and cheap debt, with fixed-rate, 30-year home loans available in the 2.9% range (if not lower).

Nationally, inventory of homes priced under $100,000 was down 32% in July from a year earlier, with homes priced between $500-700,000, down 9%. Baby boomers with some $10 trillion of equity in their homes are not selling or moving, certainly not in the midst of a pandemic. Finally, institutional home-rental firms like Invitation Homes (the country’s largest rental-homeowner, at 80,000 homes), Tricon Residential, American Homes 4 Rent, and Roofstock have been snapping up large swaths of homes in certain markets. Invitation Homes has been spending some $200 million each quarter in new acquisitions. A few graphs, capturing Case-Shiller housing data (threemonth lag), total volume of home sales, and national homeownership rates, tell a thousand words:

At this point, I see house price increases moderating in the absence of further economic stimulus or real gains in employment levels or wages, as mortgage rates have likely reached a near-term floor. The multifamily market should continue to attract tenants and maintain high occupancy rates, but rental growth will be harder to come by, and we are underwriting prospective opportunities with this perspective in mind.

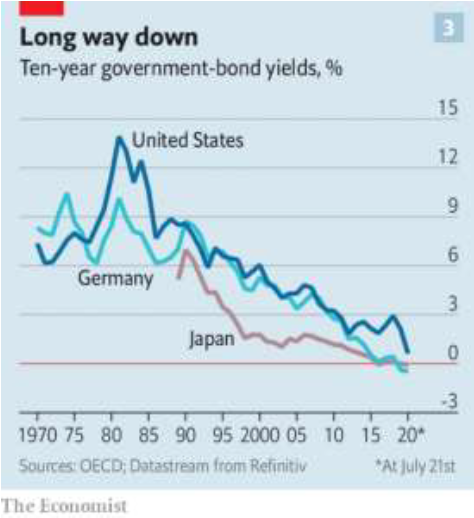

With 10-year Treasury Yields hovering around 0.70%, mortgage rates under 3.0%, and Fed assurances that low rates are here for the foreseeable future, asset values have significant foundational support

If I had told you any number of years ago that you would be able to secure a fixed-rate, 30-year home loan at a rate of between 2.50% and 3.0%, you might have accused me of having inhaled or consumed a little of California’s most infamous herb (no, not kale). Yet, here we are. 30-year mortgage rates hit a record low just last week, averaging 2.81%, the lowest rate since Freddie Mac began publishing such data back in 1971. For comparison’s sakes, the 30-year mortgage rate averaged 3.69% a year ago.

If you think mortgage rates are strictly low on single-family residential properties, I am presently refinancing an existing commercial loan on an industrial portfolio here in Southern California at a fixed rate of 3.05% for ten years. You could have pushed me over with a feather when I received that LOI. Low rates are global and even real corporate bond yields (after inflation) recently turned negative.

Many moons ago, as an undergraduate economics major, I had to learn my John Maynard Keynes macroeconomic framework (“The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”) and views that the government had a significant role in managing economic or business cycles, through its power of the purse. Over time, Milton Friedman and the monetarists, who emphasized a focus on inflation through control of money supply, found their voices in the stagflation, high unemployment, and high inflation of the 1970’s. Paul Volcker, Chair of the Federal Reserve in the 1980’s, crushed inflation by constraining money supply, but in the process, the economic downturn worsened and unemployment increased.

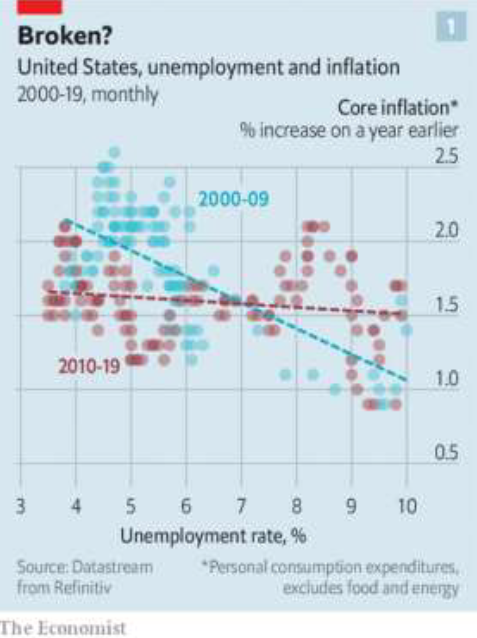

In the last 20 to 30 years, it seems that a sort of marriage of the two disciplines evolved, with both monetary policy and fiscal policy being used to manage federal spending, economic growth, interest rates, and “reasonable” debt levels, based on an overall two percent inflation target. That is until recently, anyhow, perhaps because fiscal policy has become overly politicized, leaving the federal government with fewer options in its toolkit.

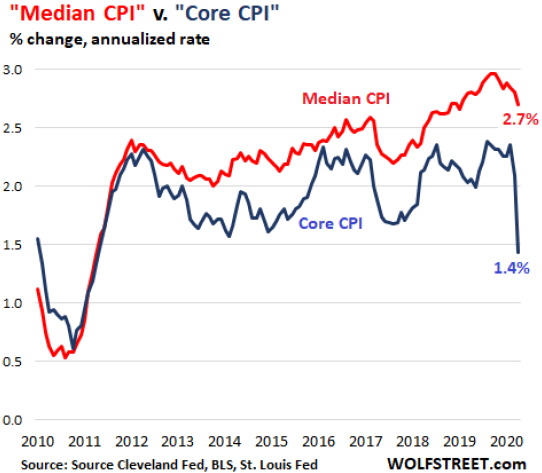

Sure enough, in an August speech, Fed Chief Jerome Powell, indicated that the Fed would ease inflation targets (read: can the 2% goal) and no longer necessarily raise rates preemptively to curtail higher inflation. Such a policy shift is not likely to be impactful in the short run, but looking back, the Fed probably would not have raised rates in the last five years as the economy recovered and fears of inflation arose. Essentially, the Fed is telegraphing that it wants core inflation above two percent to counter low growth in GDP, and that we should anticipate longer periods of lower rates and accommodative monetary policy (through 2023 at least). With core inflation presently running at less than 2.0%, and numerous economic headwinds still present, deflation remains a greater risk at the moment than any sort of significant or runaway inflation.

The punchline is clear. Low rates are here for the foreseeable future, which will provide some support for asset prices: equities, bonds, and real estate. Those seeking high yields are going to find few alternatives, and cap rates on commercial real estate investments will remain compressed. Couple low rates with excessive liquidity and you have a recipe for stubbornly high, and in certain cases (read: certain technology-related stocks), inflated asset values.

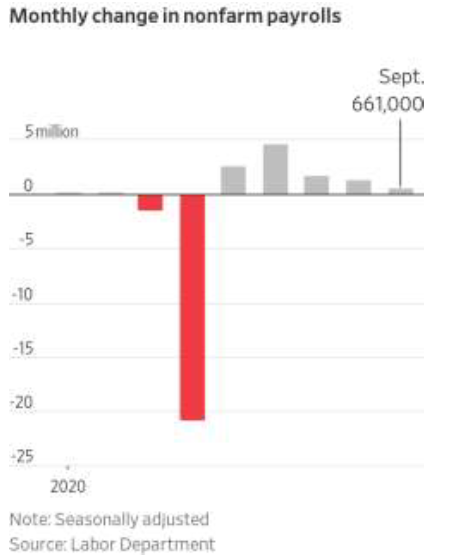

GDP and a fragile job market present the biggest risks to economic recovery and asset prices

In the face of lingering COVID infections, inconsistent policy responses across all levels of government, the absence of additional governmental intervention and stimulus, and yes, political uncertainty, the recovery in the U.S. job market has stalled. While the published principal unemployment rate improved to 7.9%, a 0.5% improvement over August figures, and half of the jobs lost since the start of the pandemic have been regained, some 700,000 workers have since dropped out of the labor force (as mentioned above), signifying that actual unemployment is far higher than 7.9%. While nonfarm jobs increased 661,000 in September, weekly jobless claims remain persistently elevated.

While third quarter GDP is expected to increase over 30%, that growth comes on the heels of a record-setting second quarter decline of 32.9%, both records since record-keeping began 70 years ago. Keep in mind that 30% growth following a nearly 33% decline still means that GDP is down more than 10% since the pandemic began. The question is what happens in the fourth quarter and beyond. At this point, I think the likelihood of a double-dip recession is significant, especially in the absence of additional federal stimulus. Without stimulus, herd immunity, or a vaccine, we will remain in an extended period of economic malaise. That is, even if we don’t experience a double-dip, hopes of a “V” or “U” recovery become significantly less likely.

Speaking of which, it’s unfortunate that government stimulus proposals have become so heavily partisan, when the economy might very well benefit from a kick in the pants

I recognize that many believe the government should take a hands-off view towards the economy and leave markets alone to their own devices, while others believe Uncle Sam and state governments ought to take a heavier hand in providing one form of economic stimulus or another. Frankly, it seems that individuals within their own political parties don’t necessarily agree on how much stimulus should be provided, if any, and/or to whom it should be directed. I fall in the middle of these two camps and believe that some form of stimulus will aid in accelerating economic recovery. One proposal that seemed eminently reasonable and logical to me was put forth from Senator Michael Bennett of Colorado, who wanted to link federal unemployment benefits to local unemployment rates. Of course, this means it has absolutely no chance of passing.

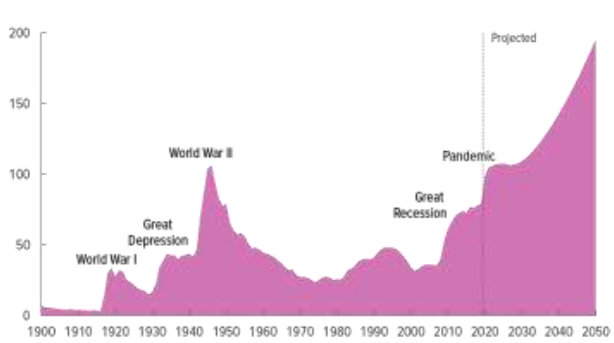

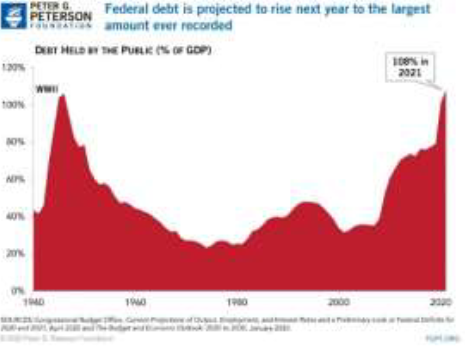

I know that growing national debt levels scare the pants out of many, though conservatives are far less focused on this issue today than they were four years ago. By 2021, if not sooner, our outstanding national debt will likely exceed the size of our entire economy for the first time since World War II.

The question becomes when are our national debt levels truly excessive? There simply is no consensus. Keep in mind that Japan’s gross debt is over 237% of its GDP, so one can argue that we have a long way to go before we are truly excessively indebted. Then again, knowing that we are quickly catching up to Portugal and Italy hardly gives me the warm and fuzzies.

So, should the government pass stimulus legislation or not? I guess it is the lesser of evils and risks in my view, and I believe some stimulus is necessary, while we can certainly debate how much and to whom the largesse should be directed. I suppose we will know soon enough. I wonder if Vegas is taking odds on whether it will happen, and if so, before or after early November.

If November’s California Ballot Measures are any indication, the public sector real estate creep is here to stay

Earlier in this memo, I half-joked about the length of the California Voter’s Guide, which includes no fewer than three very material real estate related measures: Propositions 15, 19, and 21. Proposition 15 represents the largest potential tax increase in California history. If passed, commercial properties (all residential properties are excluded) would be reassessed at least every three years, and taxed accordingly. Presently, property taxes are based upon a property’s last sale price, increased no more than two percent each year. Proposition 19 would modify property tax benefits accorded certain inherited properties, while Proposition 21 would significantly expand rent control. At this point, all three measures appear on their way to lose, and I am shedding no tears about that. While I willingly acknowledge that property tax reform is badly needed, these propositions are too onerous, and will have long-lasting negative repercussions for business and employment in the State, while failing to provide more and less expensive housing.

Meantime, any number of other ballot measures, laws and regulations across the U.S. are addressing evictions for both residential and commercial tenants, generally seeking to balance out the needs of both tenants and landlords. However, as I have said many times, there are far more tenants who vote than landlords who do so. The CDC has barred evictions for as many as 12.3 million renters through the end of the year, mostly tenants in buildings financed with federally-backed mortgages, extending protections provided by the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act passed in late March. Those protections expired in July. While these measures generally do not relieve tenant obligations to pay rent and are arguably unconstitutional (“private property shall not be taken for public use without just compensation”), it is very unclear how landlords will be able to recover delinquent rent or pursue damages from regulations ultimately determined illegal.

This is not some theoretical issue as our firm – across our nearly 4,000 units – has a number of delinquent tenants, some of whom appear to merely be taking advantage of the situation, and we are hardly finding it easy to pursue any sort of meaningful recourse against them. Moral hazard is real. We are expending significant resources to collect delinquent rents and to work with tenants as best we can, within the confines of legal and political realities.

And, of course, there are a number of other interesting tidbits and trends which impact markets, the economy, and commercial real estate

Every quarter, there are a few other relevant and material data points, trends, or tidbits that are worth mentioning and discussing. The third quarter of 2020 was certainly no exception, so without further ado, here goes:

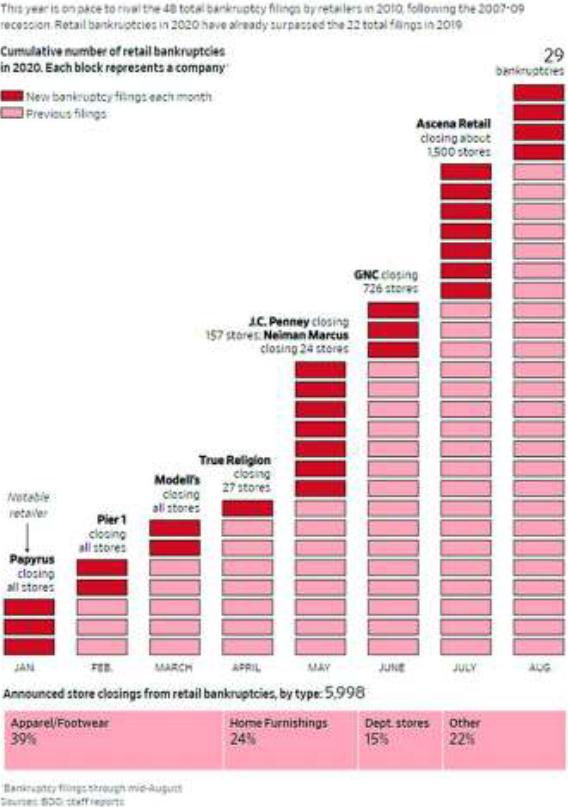

• The brick-and-mortar retail apocalypse continues: I know you don’t need me to tell (remind) you about what is happening to traditional retailers, who were being Amazoned (a new verb) and e-tailed before the pandemic, which accelerated the trend. The impact on just the job market alone is remarkable, and many of these retail-related jobs will not be returning anytime soon. 2020 is shaping up to be a banner year, and not in a good way. Here’s the sobering reality:

In time, will some of these jobs return and/or other retailers or uses occupy vacated leaseholds? Perhaps. But I don’t see any sort of “V-” or “U-like” recovery here.

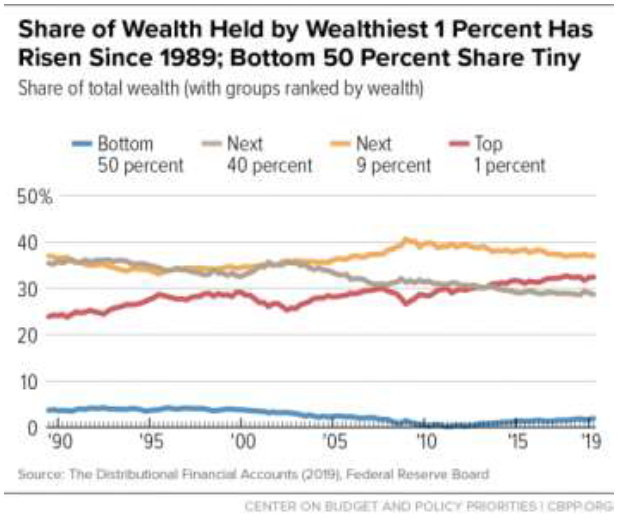

• Expanding wealth inequality may be our single greatest economic and social threat: Over the years, I have repeatedly expressed concerns about the increasing chasm

between the “haves” and “have nots” in the U.S., and the impacts it has on housing, the economy, markets, and even our social fabric. In parts of California, and frankly, throughout much of the country, we may need to modify the list to the “haves,” the “have-nots,” and the “homeless”. I drive by entire homeless encampments each and every morning here in west Los Angeles. I am certain that some of the social unrest we witnessed this past summer, some of which persists to this day is based, in part, to wealth inequality. Perhaps some will disagree with me, but I believe it is not good for the stability, if not sustainability, of our economy, neighborhoods, and political system. If there is any silver lining tied to our business, it sure is creating demand for affordable housing, and we are actively looking for investments in that space, such as our present offering in Carrollton, Texas and our upcoming attainable workforce housing offering in Victorville, California. But I am not blind to the broader potential significance and import of this disturbing trend.

I do hope that whatever comes of the upcoming election that we – politicians and voters from all sides of the aisle alike – address the wealth disparity and homelessness issues, or

expect increasing social unrest and divisiveness to become recurring realities, and I can’t see any positives in that.

• Foreign investment in our real estate markets has declined sharply over the past year: It should come as no surprise that foreign direct investment in U.S. real estate

has dropped sharply in 2020, declining by nearly 40% during the first half of the year as compared to the same period in 2019. A recent Wall Street Journal, “Foreigners Buy Fewest U.S. Homes in Years,” says it all, though it is just not single-family homes, but all types of residential and commercial real estate for which foreign buyers have lost some appetite.

Obviously COVID is playing a role, but travel restrictions and constraints on capital outflows in places like China, have certainly not helped the cause.

While many predict a bounce in foreign investment next year – we are invariably an optimistic lot, after all – I am not nearly as sanguine, though I believe the U.S. will remain a

relatively safe and attractive place for foreign investment capital. I merely think CBRE’s anticipated 2021 bounce will be less robust.

• Higher property and casualty insurance premiums are a-comin’: Between the California and Colorado wildfires, hurricanes in the Atlantic, rain and flooding in the Midwest, and COVID-19, significantly higher property and casualty insurance premiums are coming our way, and all of us will be likely impacted, certainly any and all homeowners and investors in investment real estate. According to an industry report I just read (https://www.usi.com/content/downloads/2020_PC_Market_Outlook.pdf), premiums will increase by at least 10% for most standard coverages, while properties located in areas more prone to natural disasters or “catastrophic loss,” may see premium increases of anywhere from 25 to 40%. We are seeing premium increases across our portfolio, and these higher costs are not able to be passed onto our residential tenants. Meanwhile commercial tenants under triple-net leases are going to see far higher common area charges in 2020 and beyond.

• All that glitters is gold, and it’s not just Led Zeppelin who thinks so: Since the start of the pandemic, gold prices have surged, up some 25% in 2020, hitting an all-time high of over $2,067 an ounce in August, before falling back to around $1,900 an ounce where it presently trades. The decline in the U.S. dollar, the increased federal deficit, and lower interest rates (reducing carrying costs) have all played a part in the move.

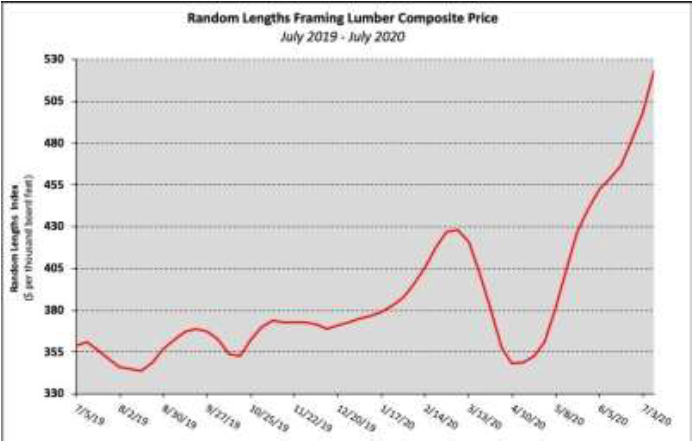

Meantime, gold is not the only commodity that has “shined” of late. Lumber futures have more than doubled since early April, and prices reached the highest level seen since record

in spring of 2018. Prices have risen because producers idled plants and saw mills in US and Canada in March, beetle infestation, and, of course, the wildfires. Lennar, the largest U.S. homebuilder (by revenue), said that it is intentionally curtailing construction and sales to avoid higher material costs, hoping to make up difference in higher future sales prices.

If homebuilders truly cut back on construction and new starts as a result of these higher commodity prices, the supply of new home inventory will be further constrained, putting

additional upward pressure on pricing of existing homes for sale.

In closing, while the next few months will bring impactful news, Clear Capital’s core investment philosophy, approach, and focus have not wavered, as we continue to focus our acquisition and underwriting efforts in the Sunbelt and in our home state of California

First and foremost, I hope that you and those in your close circle of friends and family remain in good health. That is of paramount importance, of course. I also hope that you have voted or will do so, regardless of where you sit on the political spectrum. We should never take this most sacred of rights for granted. And while I won’t tell for whom you should cast your presidential vote, I might gently nudge you to vote “no” on Propositions 15, 19, and 21, at a minimum, for those of you casting your lots here in California.

As mentioned at the outset of this memo, making forecasts in this environment is no easy task, as the outcome of the election could profoundly shift the direction of the country: economically, fiscally, and certainly, politically. I warn students nearly every quarter about the use of “Ctrl-R” and “Ctrl-D” functions in Excel, where one merely copies certain spreadsheet cells down and to the right, as though one year’s results or forecasts can be mechanically extrapolated into the future. I am trying very hard not to fall into that same trap myself.

However, whatever happens on November 3rd and thereafter, I remain steadfastly optimistic about the multifamily market and our acquisition, underwriting, and investment strategy. I am profoundly grateful to the entire Clear Capital team, which has faced the COVID-related challenges head on and worked extremely hard through some trying times. For those of you who invested in our recent Lakewood, Colorado opportunity (Falls at Lakewood), which was over-subscribed, and for those considering our present offerings, a 244-unit, affordable opportunity in Carrollton, Texas, and a 200-unit attainable workforce housing opportunity in Victorville, California, thank you for doing so, and for your continued support of our firm.

Best,

Eric Sussman

Founding Partner