I always avoid prophesying beforehand because it is much better to prophesy after the event has already taken place.

—Winston ChurchillThere are decades when nothing happens and then there are weeks where decades happen.

—Vladimir Lenin

As I reflect upon the first half of 2020, I can’t help but think about the book, “Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Change in Life and the Markets,” written by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, which I read nearly 20 years ago, when it was first published. A fairly quick read (and one that I recommend), it provided me with an appreciation for statistical aberrations and those seemingly random events – wars, financial crises, and yes, pandemics – which, while perhaps precisely unpredictable, routinely and very materially impact life, markets, and investment returns.

However, though I recognize that these “black swans,” as they are often labeled (and coincidentally, the title of one of Mr. Taleb’s subsequent books), are bound to occur over a long enough timeframe or investment horizon, I can say that neither a global pandemic nor widespread protests over police brutality and social/economic injustice appeared on my 2020 Bingo card. Over 140,000 Americans have now died from COVID-19, and records for new infections are occurring daily, most notably in Florida, Texas, and California, which, along with several other states, are in some form of economic lockdown. The deaths of Kobe Bryant and Qasem Soleimani, the Australian wildfires, the impeachment acquittal, the collapse in oil prices, and the Tiger King seem like distant memories, reflecting just how unusual (dystopian?) this year has been, with each day feeling a bit like Groundhog Day. I have never asked myself, “what day of the week is it today?” more than I have in these past four months. Thank goodness the murder hornets have not yet reached our shores.

In summary, the second quarter of 2020 was one that most of us would rather forget, distinguished as it was by several inauspicious records. We have already witnessed more bankruptcies this year than in all of 2008, the year that Lehman Brothers – the largest single bankruptcy of all time – failed, along with record levels of unemployment and the sharpest quarterly decline in GDP in U.S. history. The second quarter Chapter 11 graveyard includes firms such as Hertz, JC Penney, Neiman Marcus, Frontier Communications, Chesapeake Energy, Intelsat S.A., and Diamond Offshore. I am not exactly going out on a limb when I suggest that there will likely be several more names added to this list before 2021 arrives, not a moment too soon.

In fact, the WSJ and Coresight Research report that U.S. retailers are on track to close as many as 25,000 stores this year, more than double the previous record. However, it is simply too early to be sure what the ultimate fallout will be. Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that JP Morgan, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo have set aside some $28 billion in reserves to cover anticipated pandemic-related losses, adding over 30% to previously accrued loan loss allowances.

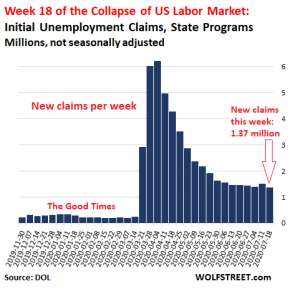

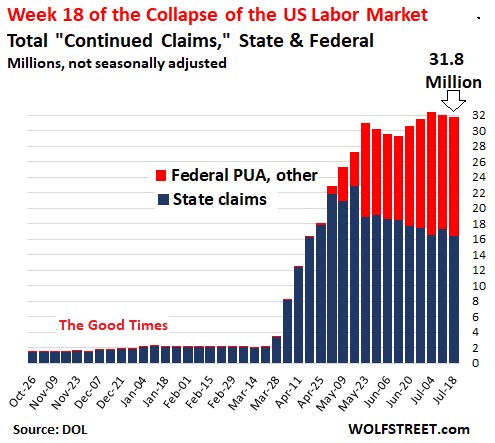

Although the June unemployment rate of 11.1% represents a marked improvement over the 14.7% and 13.3% rates reported for April and May, respectively, these employment gains will likely prove transitory as more cities and states mandate closures (e.g., Atlanta, West Virginia), while others reimpose them (e.g., California, New Mexico, Oregon); the requirements that employers maintain employment levels under the Paycheck Protection Program burn off; and, both federal and state unemployment benefits expire (the $600 additional federal unemployment stimulus expires this month). Just this week, an additional 1.4 million claims for unemployment were made, representing the 18th straight week of unemployment claims exceeding one million. Not surprisingly, the U.S. economy shrank dramatically during the quarter, and while final figures are not yet available, consensus estimates are that U.S. GDP declined over 40% in the second quarter. Ouch.

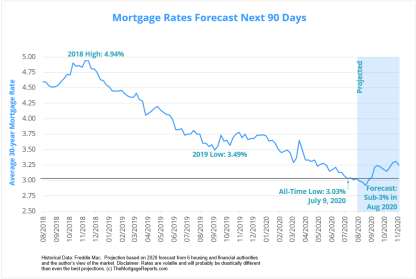

And if this were not enough, CNBC recently reported that 32% of U.S. households missed their July mortgage payments, at least through the first week of the month. However, because most mortgages allow a ten-day grace period before late fees apply, we cannot be sure just how deep or pervasive the problem might be, at least not yet, but I can’t imagine that mortgage delinquencies on single-family homes, hotels, and retail assets will be anything but significant, if not record-setting, despite recent 30-year single-family residential mortgage rates recently hitting an all-time low of 2.98%. I recently read that over two-thirds of Americans have less than $1,000 in savings, so unless labor markets continue to rebound, which appears unlikely, or unemployment benefits are extended, both mortgage and rental delinquencies can only go in one direction.

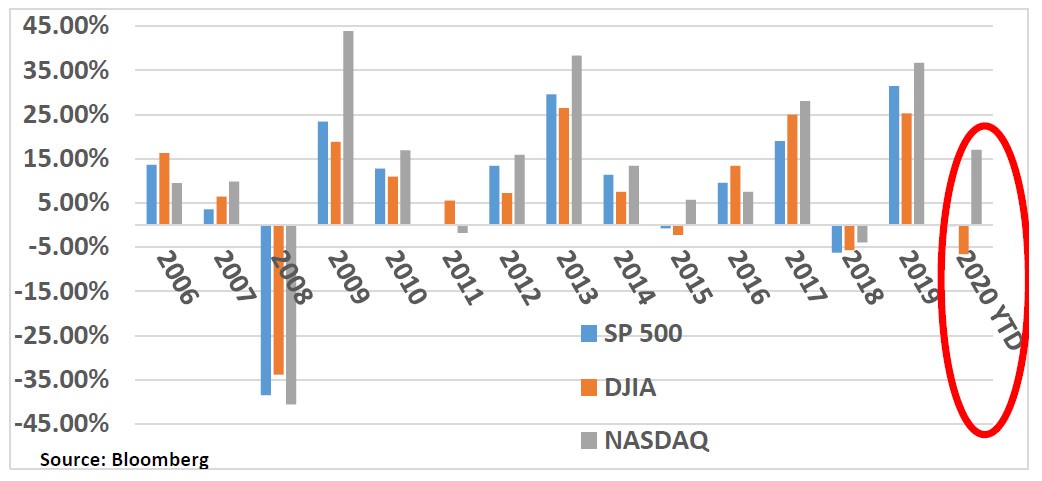

Perhaps the only bright spot, and one that even I find surprising, has been the performance of the domestic equity markets, which have rebounded sharply from their March lows. While the Dow is down approximately 6.4%, the S&P 500 is up fractionally, about 0.3%, while the NASDAQ is up a truly remarkable 16.8%. Keep in mind that the equity markets were down nearly 30% earlier this year, so the rebound has been noteworthy, if not downright astonishing.

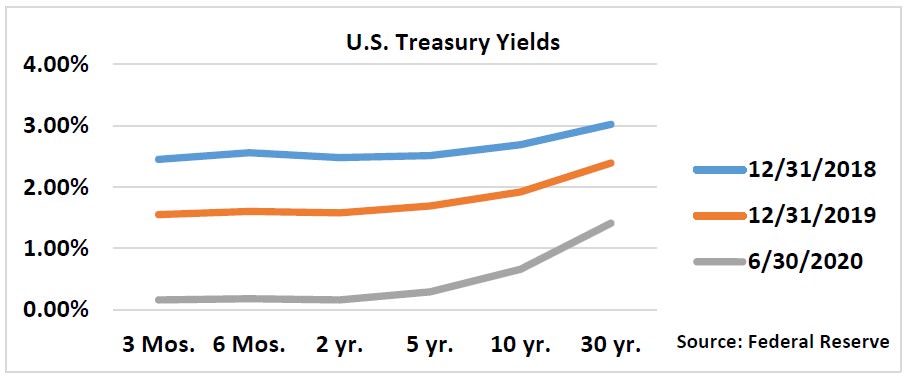

While the equity markets are forward-looking and perhaps anticipating a COVID-19 vaccine, persistently low interest rates (10- and 30-year Treasury yields ended the second quarter at 0.66% and 1.41%, respectively, essentially flat from the end of the first quarter) and continued Fed largesse, there does seem to be a disconnect between the present economic environment and recent equity returns. Perhaps it is simply that investors are that desperate for yield and return. Perhaps it is algorithmic trading. Perhaps it is novice investors (read: speculative) trading via Robinhood. Perhaps it is all that liquidity and Fed monetary policy. Frankly, it is likely a combination of all these factors.

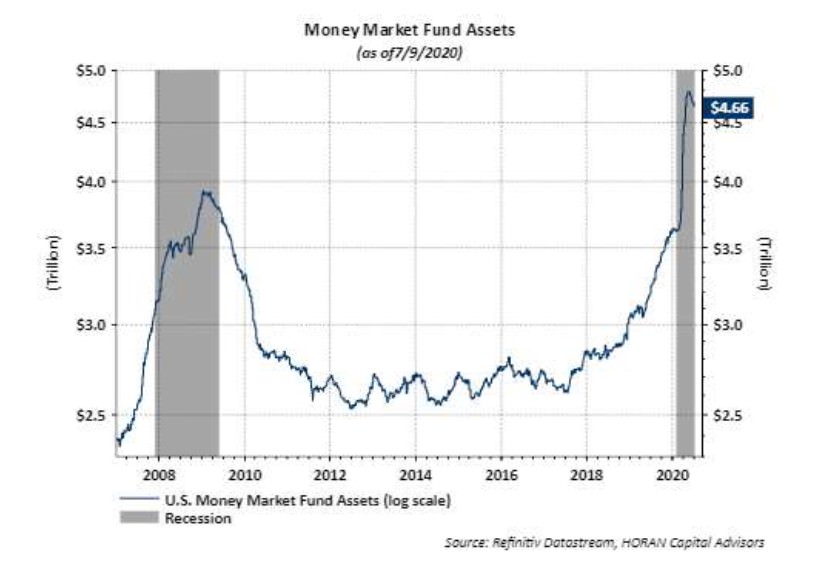

Keep in mind that even with the strong equity market performance, domestic money market assets remain at record levels, in excess of $4.6 trillion, some 40% more than prior year levels. Presumably, these assets sitting on the sidelines will ultimately find their way to more risky investments, including equity markets and real estate. Remember that in the latter half of 2019, Blackstone, Goldman Sachs and others raised record levels of capital (over $20 billion) in various real estate funds, and just recently, Blackstone’s secondary and funds solutions business, Strategic Partners, raised another $1.9 billion to acquire secondary interests in real estate funds and assets. In short, liquidity and investable capital remains plentiful and should provide some foundation for asset values.

Meanwhile, we continue to maintain strong physical occupancy and rental collection rates across our portfolio (over 90%), which compare favorably to broader industry trends. The National Multifamily Housing Council disclosed last week that 87.6% of apartment households made full or partial rent payments by July 13th, based on a survey of 11.4 million units across the U.S. However, it is very difficult to forecast what lays ahead without i) clarity as to when or if a Coronavirus vaccine is found; ii) how or when it might be subsequently administered; iii) what sorts of government stimulus (at every level), if any, might be forthcoming; and, iv) local, state and federal limits on residential evictions. The extraordinary politicization of the pandemic and the added uncertainty of an election year present additional forecasting challenges. We are acting accordingly, continuing our considerable efforts on tenant retention, asset management, and expense control.

Looking forward, multifamily assets should continue to perform fairly well, certainly relative to other classes of real estate. While high unemployment and weak GDP figures present clear headwinds for the remainder of 2020 and likely into the first quarter of next year, low interest rates, significant liquidity, reduced residential construction, challenging underwriting for prospective homebuyers, fewer people relocating for new jobs (or staying put due to health concerns), continued migration from the coasts to less expensive housing markets, and renter demand in secondary, tertiary, and yes, quaternary markets – those on which Clear Capital focuses – should present tailwinds for multifamily assets, at least in many markets, and a foundation for continued high physical occupancy levels. The biggest question is whether that same percentage of rents is actually collected in the absence of economic recovery and a renewal or extension of unemployment benefits or other governmental largesse.

All in all, multifamily rents, including the impact of move-in offers and rental concessions, will likely soften during the latter half of 2020 before rebounding next year, and we are underwriting new opportunities through this conservative lens. At this point, however, I do not see significant distress in asset values. During the Great Recession, distressed asset sales represented about a third of transaction volume, according to CoStar, and median cap rates rose between one and two percent across asset types. But this downturn is different in that it arrived via supersonic jet and will probably play out like snail mail because of concerted intervention by both the public and private sectors. According to Real Capital Analytics, overall deal volume fell 71% in April, as compared to the prior year, though prices on consummated transactions remained steady, as reduced demand was offset by reduced inventory of assets for sale. With so much cash sitting on the sidelines and interest rates so low, I believe that investors waiting for bargain basement prices will find themselves waiting for Godot.

Finally, despite the pandemic, or perhaps because of it, we continue to evaluate dozens of potential opportunities each and every week, most of which simply don’t satisfy our underwriting criteria, especially in this new reality. However, we are teeing up a couple of attractive offerings, one in Carrollton, Texas (we circulated a teaser about this opportunity several months ago) and another in Lakewood, Colorado so keep an eye out for those opportunities, in which I hope you might consider participating.

Beware of predictions that claim that COVID-19 will forever alter the way we live, do business, and interact. I anticipate that life will return to normal in due time

In 1974, a sociologist at the University of Houston, Jib Fowles, coined the term “chronocentrism”, which he defined as “the belief that one’s own times are paramount” and “that other periods pale in comparison.”1 During the last few months, I have read numerous op-eds proclaiming that the Coronavirus will forever alter the way we live, work, and play. Some have predicted that people are going to permanently flee urban centers for the suburbs, forever work from home, abandon brickand- mortar retailers and shopping malls, and travel less frequently, decimating the hotel, retail, and office markets. We will never hug or shake hands again. Each time I read or hear these bold proclamations, I roll my eyes. You need not look any further than at some of the large social gatherings routinely occurring in the face of the pandemic, including people actually hosting COVID-19 parties (talk about an invite that ought to be declined “without regret”), to get a good glimpse of human nature. Imagine how we will behave assuming a vaccine is found.

In the 2000’s, when suicide bombers routinely attacked cities like Baghdad and Tel Aviv, or when France encountered terrorism just a few years ago, most people went about their daily lives. Many countries with high levels of violent crimes (e.g., Brazil, Guatemala, Mexico) are not exactly known for boring, staid night lives. Old habits are simply hard to break, and we are social creatures by nature. In five years, I predict there will be as many mass gatherings as there are today, and travel, while perhaps not returning back to 2019 levels, will have substantially rebounded. And in 10 years? COVID-19 will likely (hopefully) be a distant memory.

Will people more routinely wear masks, especially during the winter flu season? Will universities perhaps change instruction approaches, including ending the fall quarter/semester at Thanksgiving, or providing more hybrid educational platforms, combining live and remote instruction? Will we wash our hands and use hand sanitizer more often, even carrying around Purell everywhere we go? Sure. But if anyone thinks that virtual conferences, meet-ups, and happy hours are going to act as permanent substitutes for the real deals, I think they are nuts. As I told my students at the end of the spring quarter, I don’t think employers are going to hire them – ostensibly the best and brightest – so that they can work from home, in isolation. Innovation and solving challenging business problems require collaboration and networking, which is far more effectively accomplished in person.

Perhaps a quick anecdote will highlight the flaws of chronocentrism. For better or worse, I have joined several private groups on Facebook, including one which is purely nostalgic, focused on the San Fernando Valley here in Southern California (where I grew up) during the 1970’s and ‘80’s. I imagine many of you are members of similar groups. Anyhow, as I was recently scrolling through various posts, including countless photographs of life back then, I noted how much had changed, how many retailers I once frequented had come and gone, and how groves of orange trees had been converted to single-family residential housing tracts. However, I also noticed how much essentially remains the same.

In about ten minutes of scrolling through these old photos, I noted all the retailers now relegated to the dustbin of history, some of which you will likely recognize and remember: Zody’s, GEMCO, Woolworth’s, Fedco, PicN’Save, Pacific Stereo, Carpeteria, Fotomat, and Federated Stores, all replaced by new retailers like Costco, Best Buy, Bed, Bath, & Beyond, and Ashley Furniture. And now I read that Bed, Bath, and Beyond will be shuttering 200 stores this year, so the cycle of evolution, devolution, rebirth, and rebuilding continues anew. As I have said countless times, the only constant is change when it comes to how people live, work, shop, and even invest. We should just be a tad cynical when people predict that things “will never be the same” or will be “forever changed.”

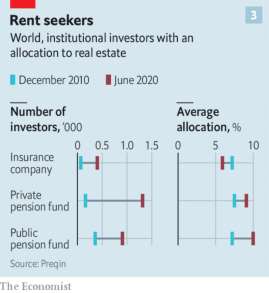

A recent Economist article noted that over the past two decades, the investment world fell “in love” with property, and then asked rhetorically whether “it is the end of the affair?” The article included a couple of graphs to highlight the point. My terse response is “no, it is not the end of the affair.”

Anecdotally, when I started teaching real estate investment and finance courses at UCLA Anderson in the spring of 1996, we offered but a single elective class each year that attracted about 35 MBA students, and I don’t remember if any of them pursued real estate as a career. Today we offer nine different real estate electives, enrolling hundreds of students each year, many of whom end up working in real estate, whether on the buy, sell, or advisory sides of the industry. The shift has been remarkable, as MBA students and their employers also appeared to “fall in love with property.”

Do I see this trend reversing? No, I don’t. Perhaps it is my views on chronocentrism. Perhaps it is the impacts of the Internet and technology on the industry. More likely, it is due to the increasing challenges the industry faces (e.g., increased local regulations, need for repositioning or redevelopment of assets and markets) which will require creative solutions, rigorous analysis, and significant capital, just the sort of resources that institutional and quasi-institutional investors (and yes, MBAs) can bring to bear to real estate markets.

Multifamily assets should continue to be a relative bright spot in an otherwise challenging commercial property market

Not surprisingly, the global pandemic and resulting economic fallout has been especially hard on many segments of the real estate market: hospitality, restaurant and retail, office space, in addition to student and senior housing. Not surprisingly, occupancy in senior housing hit a 15-year low last week, to less than 85%. For the week ending, July 11th, the national hotel occupancy rate was 45.9%, and in the 25 largest markets, just 39.2%.

Meanwhile, the multifamily market has weathered the storm fairly well, with both physical occupancies and rental collections generally exceeding 90%. In many markets, collections have exceeded 93% (e.g., Sacramento, Virginia Beach, Denver), while in others (e.g., New York, New Orleans, Las Vegas, and Orlando), markets disproportionately tied to travel and tourism or those without industry diversification, landlords have struggled with collections. Needless to say, the combination of shelter-in-place orders, furloughs and job losses, eviction moratoriums, and general fear and uncertainty are responsible.

Nationally, multifamily rents have declined 0.3% since March, when the pandemic began. At first blush, this decline seems modest. However, keep in mind that the second quarter is usually strongest for multifamily rents due to seasonality. Since 2014, rental growth between March and June has ranged from 1.0 to 1.7 percent, highest of any other quarter during the year.

Over the past twelve months, national apartment rents have increased by just 0.2 percent, by far the lowest year-over-year growth rate over any of the past five years. Landlords, including Clear Capital, have had to respond to this new reality by reducing rents and offering increased concessions (e.g., free rent) in order to fill vacancies or renew existing leases that are expiring. Not surprisingly, changes in rents vary markedly by location, much like rental collections. Of the 100 largest cities, 56 experienced lower or flat rents, and in 88, rents are growing slower than last year. Here in Los Angeles, rents dropped 3.3% in May, following a drop of 0.8% in April, and at the end of the second quarter, the vacancy rate exceeded 5.5%, the highest ever witnessed in the market, according to CoStar.

Longer term, the pandemic’s effect on rents will depend heavily on how quickly the economy is able to recover. My sense is that the recovery will be more drawn out than many (including yours truly) had hoped, making it likely that we will witness many households facing financial hardship begin to seek more affordable housing, increasing demand for apartments generally, especially Class-B and C units. Class A or higher-end luxury units will find filling vacancies more challenging. Migration from the coasts, a trend I have discussed for years, will accelerate.

We will also see a significant slowdown in new household formation and fertility rates (see additional discussion below), as more Americans move in with family or friends to save on housing and other costs. As longer-term remote work gains traction, we may also witness a shift away from expensive downtown markets and toward more affordable suburbs, though I am skeptical that such a move will persist longer-term. Again, I am mindful of both chronocentrism and economic and social realities, which may conflict with one another.

Other housing data remains decidedly mixed

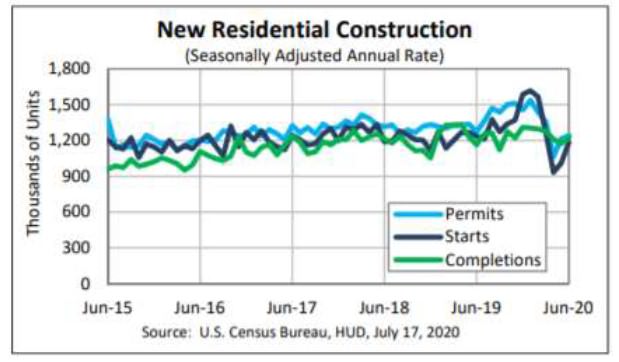

Generally, data surrounding housing – permits granted, construction starts, units completed, sales volumes, pricing, and occupancy levels – is really a mixed bag depending on the particular data set and related timeframe. On the one hand, the Commerce Department just announced that nearly 1.19 million new housing starts commenced in June, following very steep declines in March and April and a modest recovery in May. However, even after a second consecutive month of growth, construction activity remains four percent below the prior year. Building permit applications follow a similar track, rising 2.1% in June to 1.24 million units, well off the April lows.

Last Thursday, the National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo survey of builder confidence jumped for the second straight month in July to a reading of 72, near pre-pandemic levels (any reading above 50 indicates a positive market). The index had plunged 42 points in April to a reading of 30, the largest single monthly change in the history of the survey.

Finally, to show just how mixed housing data is, we can look at two bookends, the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City. In June, home sales in the Bay Area surged nearly 70% over May’s results, and prices rose 3.6% from May and 4.2% from the prior year, all representing sharp turnarounds from the previous three months when Bay Area sales fell 51%, 37%, and 12%, respectively, as compared to the same periods last year. I suspect that strong performance in the NASDAQ, coupled with the ability of many tech employees to work remotely, have contributed to these favorable results. Meanwhile, in Manhattan, the number of closed sales in the second quarter was down 54% compared to last year, the largest decline in 30 years, while median sales prices declined 17.7%, according to brokerage firm Douglas Elliman. NYC apartment leasing was down 76% in June, year-over-year.

Not surprisingly, the economic and market uncertainty has made lenders significantly more cautious in their underwriting

According to the most recent data from the Mortgage Bankers Association, released this past week, commercial and multifamily mortgage bankers are expected to close approximately $250 billion of loans this year, a 59% drop from 2019’s record volume of $601 billion. Total multifamily lending, including loans made by small and midsize banks, is expected to decline 42% to $213 billion in 2020, a sizeable drop from last year’s record of $364 billion.

As anticipated, lenders are employing far more conservative underwriting standards, hearkening back to 2008 and 2009, though lenders are not grappling with the same sort of balance sheet challenges they encountered back then. For example, where lenders might have been willing to previously lend 70-75% of a property’s value, they now require greater borrower equity, and may only lend 65-70% of a property’s value, while requiring additional reserves, including anywhere from six to 12 months of pre-funded debt service and reserves (e.g., property taxes, insurance). Most lenders have increased the “spreads,” the additional pricing premiums they might require over a relevant underlying index, on both fixed and variable rate loans. For example, where Fannie might have charged an interest rate of 1.90% over the 10-year Treasury yield prior to the pandemic, they are now charging an additional 50 to 60 basis points on such loans. Life companies, popular fixed-rate, longer-term debt providers to multifamily operators, are offering 60% loans, with 10% debt yields, far more conservative than prior underwriting standards.

In short, lenders are also engaged in “price discovery,” as they underwrite loans in an increasingly uncertain marketplace. I expect this underwriting waltz to continue through the remainder of 2020.

Inflation remains tepid at present, but unprecedented quantitative easing and action by the Federal Reserve significantly raises the specter of future inflation

While the 0.6% increase in the June Consumer Price Index (CPI) may seem surprising, core inflation, excluding volatile food and energy, rose a far more modest 0.2%. Through the first half of the year, annualized core inflation is up 1.2%. At this point, it really appears to be a tale of different markets: that for financial assets, consumer goods generally, and finally, for food and energy. While modest inflation is desirable, greater growth in economic activity and higher inflation, closer to 2.5 to 3.0%, should be our target.

During the last decade, the CPI increased 19%, or 1.8% per year, below the 2.0% target set by the Fed, reflecting the impact of those three A’s I have mentioned several times in the past: Amazon, automation, and artificial intelligence, which in turn resulted in increased efficiencies and flat real wages. Meantime, the S&P 500 was up 188%, or nearly 19% per year, while commercial property values increased 175% as measured by MIT’s NCREIF (National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries) Index.

Once again, it seems that we have both substantial inflationary headwinds and tailwinds. On the one hand, those three A’s are not going away anytime soon, and if anything, the pandemic will likely intensify their impacts. Clearly we are now using Amazon more often than we did before March, as we make more than good use of our Prime memberships. On the other hand, the Fed’s liberal use of their unique printing press, adding trillions in liquidity to the markets, their balance sheet, and our debt, has to ultimately and meaningfully impact markets and inflation, principally financial assets and markets (including real estate).

More than a handful of us remember the late ‘70’s and early ‘80’s and the sky-high interest rates and inflation that period experienced, if not Studio 54, polyester slacks, and bell-bottom jeans. My concern is that we are going to experience substantial asset inflation in 24 to 36 months from now, once a vaccine for COVID is released, life returns to “normal,” and all that liquidity now sitting in cash and money market funds leaves the sidelines. It is one of the reasons I believe asset prices will not witness significant declines in the short- to medium-term, and will see even higher asset values by the end of 2021, and precisely why we remain committed to invest in what we believe to be attractive investment opportunities today.

Even without the arrival of murder hornets, local, state, and federal politicians have been busy, busy bees

Since the start of the pandemic, more than 25 states have passed some sort of eviction moratoriums, preventing landlords from evicting tenants who have not paid rent due to COVID-19. Not surprisingly, these include those states with larger renter populations (e.g., California, Texas, and New York). In some states, like Nevada, the moratoriums also apply to commercial tenants. Meanwhile, the FHFA (Federal Housing Finance Agency), the federal agency overseeing federallyinsured

loans (e.g., Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) has extended the moratorium against foreclosure or eviction for those with such loans through August 31st, extending the original July 25th deadline.

The million (trillion?) dollar question is what happens once these various moratoriums expire? I have read that some 23 million renters could be evicted from their units and millions more could lose their homes. I anticipate that landlords, lenders, and government at all levels, will work together to prevent this from happening, but that remains to be seen. If the government takes too heavy of an interventionist hand, markets will be substantially disrupted, and lawsuits filed. In New York and Los Angeles, landlords have sued to overturn these moratoriums, but it is hard to assess their impact, since courts are essentially closed, and moratoriums will presumably be lifted before the cases are actually heard.

It is impossible to summarize all of the various regulatory initiatives that politicians are proposing to deal with the pandemic’s impact on homeowners and both residential and commercial tenants alike. Here in California, politicians have proposed any number of bills, including the following:

• SB 1410, the COVID-19 Emergency Rental Assistance Program: would give tax breaks to landlords for forgiving rents and halting evictions, provide for direct payments to help tenants who cannot pay their rents, and allow tenants ten years to repay debt to the state. The estimated cost to taxpayers would be up to $10 billion over the life of the program.

• AB 1436, Tenancy: Rental Payment Default: would ban evictions until April 2021, or three months after the state of emergency ends, whichever comes first. Tenants must prove their financial hardships were caused by the pandemic under the bill and would be given an additional 12 months to repay back rent, and landlords could collect the debt through civil courts. Property owners would be banned from evicting residents for unpaid rent due to COVID-19.

Meantime, a new statewide rent control initiative, the “Rental Affordability Act,” will appear on this November’s ballot. If passed, landlords will not be allowed to increase rents to market rates when a tenant vacates a rent-controlled unit, which would include single-family homes and condominium units. Instead, the ballot measure limits rent increases of vacated units to five percent per year.

Outside of California, the most far-reaching political maneuver comes from Ithaca, New York, a smallish community of 30,000 residents upstate, which passed a resolution that requests the New York State Department of Health to authorize their mayor to forgive rent debt from the last three months for tenants and small businesses, the first city to actually propose canceling rent during the pandemic. This resolution appears unconstitutional on its face.

Anyhow, I expect governments at every level to be under tremendous pressure to act and pacify their voting base, especially in such an important election year, which means that any number of tenant-friendly bills will be proposed and some passed. I further anticipate that politicians will try to thread a challenging needle in so doing, knowing that constitutional challenges and litigation await them if they push things too far. Stay tuned.

And, as usual, just when I think I should wrap up a memo, I realize that there are a few other noteworthy data points or issues, whose impact on multifamily real estate and perhaps all else, remains to be seen

One of the things I like most about real estate is that it is impacted by nearly everything, from politics to economics to sociology to psychology, and so I like to end these memos with food for thought, at least for those of you who have gotten this far…

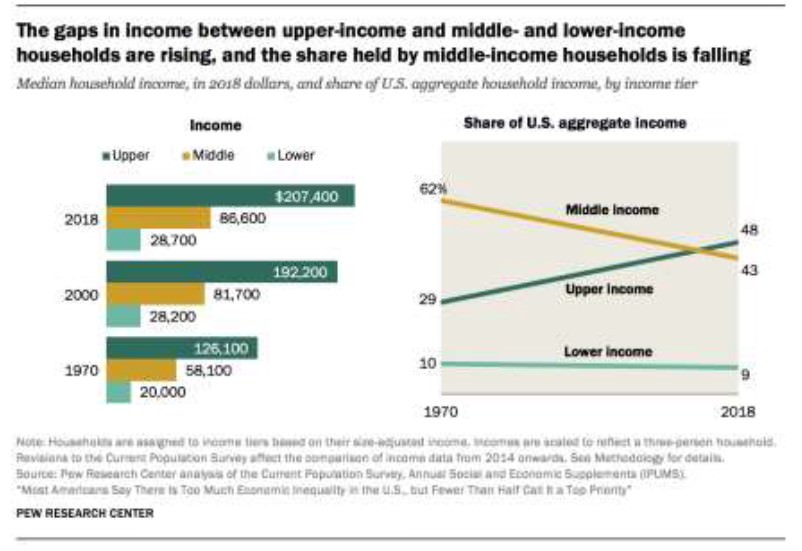

• Wealth inequality: In previous missives, I have expressed the view that expanding wealth inequality poses the greatest threat to our economy, our political systems, and overall stability. I still feel that way, as I am very unclear as to how a true democracy can persist without a strong middle class, which in turn requires greater wealth equality, it seems to me.

The interesting question is whether COVID-19 will exacerbate the trend towards greater wealth inequality, or will the pandemic result in greater wealth distribution? Thus far, it seems to be the former, with financial markets steadying, and the NASDAQ actually up sharply for the year, which principally benefits owners of these assets, i.e., the wealthy. Meantime job losses and the virus itself have and will most significantly and disproportionally impact the working class and poor, including populations of color.

One historian and faculty member at Stanford, Walter Scheidel, has argued that only four forces have managed to sustainably reduce wealth inequality: war, revolution, state failure, and pandemics. Whether there might be causation or correlation issues here, I will leave that for another day, but his thesis is interesting to note. The Great Depression led to “welfare capitalism,” an increase in safety nets, and more unionized labor. By 1950, according to the Economist, the top 0.01% of the wealthiest Americans controlled about 2.3% of the nation’s wealth, less than a quarter of what they controlled in the Roaring ‘20’s.

Obviously, this changed over time, as the data clearly demonstrates, and the disparity accelerated after the Great Recession, impacted by everything from Federal Reserve policy, the propping up of corporations and banks, the increase in automation and artificial intelligence, the weakening of labor and unions, and flat real wages. Downturns are especially rough on those entering or exiting the labor market, and this pandemic feels no different. Perhaps it depends on how the government ultimately responds to the pandemic and changes it will bring, at least in the short- to medium-term. To the extent welfare capitalism and safety nets are expanded over the next couple of years or not may ultimately be most impactful on wealth inequality.

Finally, I would simply note that as owners of principally Class B, workforce housing, we certainly benefit from our actual and prospective tenant’s greater wealth and financial wherewithal.

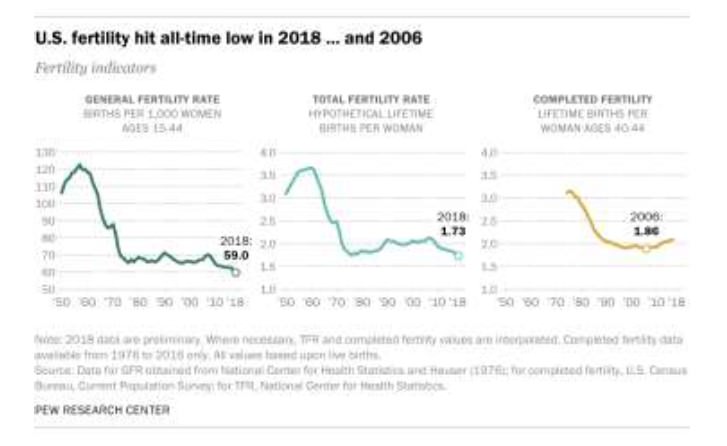

• Fertility Rates: Last year, I presented some data on the declining fertility rate in the U.S. and discussed its possible ramifications and impact on everything from future GDP growth rates, housing needs, and immigration policy. One need not look further than Japan to see the impact of declining birthrates and an aging demographic on economic growth.

• Unfortunately, data released in late May indicates that total U.S. births in 2019 fell to the lowest levels in 35 years, while the general fertility rate (births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44) fell to its lowest levels since the federal government began tracking data in 1909. This does not bode well for future growth (including demand for housing), and the U.S. needs to seriously rethink immigration policy sooner rather than later. I recently read that even at a fertility rate of 2.1 (2.1 children born to each woman living through child-rearing years), the population will actually decline.

• Cargo Issues, Imports, and Impact: In March, U.S. imports from Asia fell to their lowest levels in seven years, as retailers and manufacturers canceled orders of non-essential products. In fact, cargo volumes at U.S. ports are expected to drop by 20 to 30 percent yearover- year in the first half of 2020, according to the American Association of Port Authorities. Year-to-date imports from China are down 37 percent compared to the same period in 2019, and Mexico is now America’s number one trading partner. In fact, twice this year, import volumes for the Laredo, Texas port-of-entry surpassed those for Los Angeles County ports, the nation’s largest international gateway for inbound products.

The excess of inbound consumer goods presents a potential for a national bottleneck of loaded containers throughout the U.S. port system, as some retailers and manufacturers are failing to pick up merchandise ordered due to lack of storage space. Consequently, demand for industrial space to be used strictly for storage has increased, at least anecdotally, based on conversations I have had with local brokers, who have also told me that local developers here in Southern California are moving east to places like Banning, Beaumont, and Perris in the Inland Empire to build very large (million square feet plus) warehouse facilities and converting retail stores near consumers to “last mile” fulfillment centers.

In the longer-term, COVID-19 might result in more on-shoring of critical supplies and nearshoring of many products in Mexico which have historically been produced in China.

In conclusion, the remainder of 2020 will likely be historic, between the November election, the pandemic, and the search for a COVID-19 vaccine

I believe it was Confucius who expressed his wishes that each of us should “live in interesting times.” Well, I don’t think many of you would argue with me that if the first half of 2020 has been “interesting,” while simultaneously supporting the notion that Confucius might want to reconsider this particular philosophical musing. That is, I think we all would probably prefer something a tad less interesting than what we have individually and collectively experienced during the first half of

2020.

In any event, I remain optimistic and hopeful that so many brilliant minds working around the globe to develop a vaccine will prove successful. However, in the meantime, the politicization of the pandemic, along with the uncertainty as to when a vaccine might be found and broadly administered and how long it might take for things to return to “normal” thereafter, are making precise forecasts challenging.

However, I know that when there is broad consensus as to what is to be, something different is bound to happen, and therefore, widespread uncertainty creates potential opportunity, and should be embraced as much as it might be feared. Meanwhile, I feel fairly confident that low interest rates, coupled with the Fed’s affinity for money-printing and the significant liquidity already sitting on the sidelines, will compel higher prices for financial assets and real estate looking out two to five years, once the pandemic ends. And it will end.

Two final thoughts. One, please keep your eyes out for a couple potential offerings that we believe are attractive opportunities; and two, and far more importantly, the entire Clear Capital team hopes that you and those close to you remain in good health.

Best,

Eric Sussman

Founding Partner