“There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.”

-Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

“Value-add multifamily real estate is a canvas of potential waiting to be transformed into a masterpiece of profit and social impact."

-Fictional quote created by ChatGPT

“Uncertainty is the only certainty there is, and knowing how to live with insecurity is the only security.”

-John Allen Paulos

I have often said that the only constant in life and markets is change and my, oh my, did the first quarter of 2023 live up to that adage, trite as it might be. In what seemed to be the blink of an eye, we had the beginning and apparent passing of a banking crisis, the introduction and seemingly widespread use of ChatGPT, an eerily effective artificial intelligence tool, and the historic indictment of a former president. To put it in college basketball terms, we experienced several March Madness moments during the most recent quarter. These whiplash-like news events echo that famous quote from one of the characters in Ernest Hemingway’s, “The Sun Also Rises,” who responds when asked about his financial woes and how he went bankrupt: “Two ways. Gradually, and then suddenly.”

Since there are lots of newsworthy tidbits to cover, perhaps I should just get on with it and summarize the highlights, or lowlights, from the quarter.

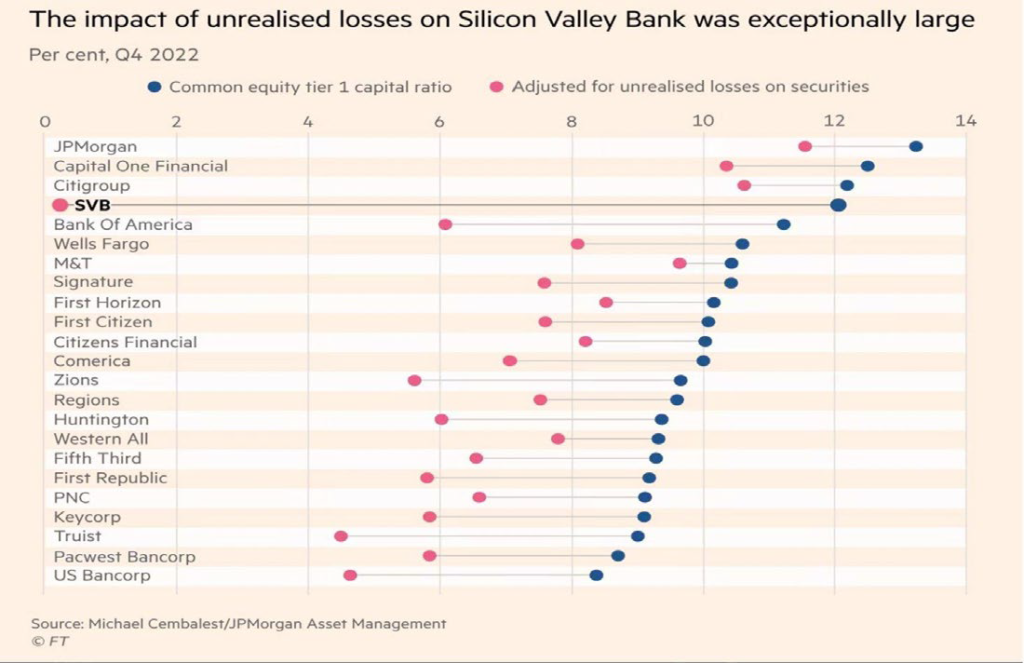

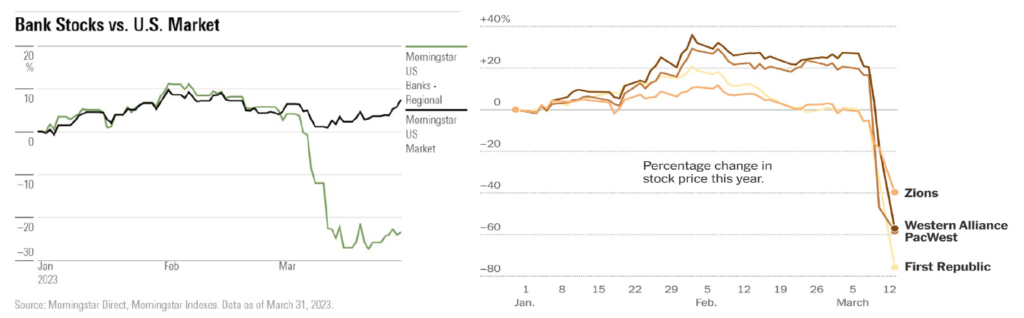

• In a matter of days in mid-March, Silicon Valley Bank went down the proverbial tubes following a bank run (or perhaps more aptly described as a “mouse click stampede”), representing the second largest bank failure in U.S. history and the largest since the Great Financial Crisis. Two days later, Signature Bank, not wanting to miss out on the fun, was also forced to close its doors. A combination of poor risk management (mismatching of asset and liability duration, excessive investment in shorter-term Treasuries and/or long-term fixed rate loans) and related unrealized losses, technological change, anachronistic FDIC insurance and financial accounting rules, and underlying bank fundamentals (e.g., high leverage, thin margins, asset illiquidity) not only sealed their fates, but revealed fundamental risks across the entire banking industry, especially among smaller, less diversified regional and community banks (e.g., First Republic, Zion’s, Pacific West).

2 | P a g e

Not surprisingly, bank stocks were crushed during the quarter, with the KBW Nasdaq Bank Stock Index down nearly 35% year-to-date. The impact of these recent events will reverberate during the remainder of 2023 and 2024 through decreased bank profitability (if not additional failures), reduced lending activity, and increasing withdrawals of deposits, all increasing the risk of recession and overall systemic risk.

Across the pond, Credit Suisse, the global investment bank and financial services firm, was purchased by UBS in a bailout transaction brokered by the Swiss government. Bank runs and related contagion are indeed a thing. Fortunately, quick Fed intervention and the collective efforts of other banks to prop up competitors apparently saved the day here at home, at least for the time being.

Specifically, a group of 11 financial institutions, including B of A, Well Fargo, Citigroup, and JP Morgan agreed to deposit a total $30 billion in First Republic to demonstrate confidence in the banking system and First Republic, specifically. I cannot recall ever witnessing anything comparable. Sure, Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway lent $10 billion to Goldman Sachs and General Electric during the Great Financial Crisis, but that was quite a different story. In any event, bank stocks seemed to substantially stabilize during the last half of March. Given the recent positive earnings announcements from JP Morgan and Citibank, it may end up being a “tale of two types of banks” or the financial equivalent of Beauty and the Beast, where large, diversified, money center banks end up benefitting from the market turbulence at the expense of smaller community and regional institutions.

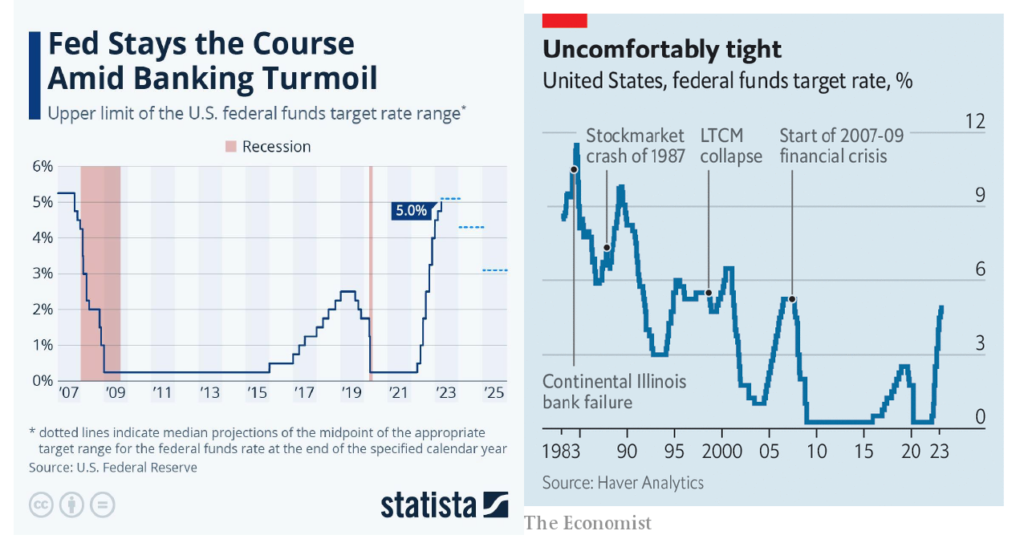

• The Federal Reserve, in the wake of the crisis, short-lived as it might have been, was compelled to rethink its sledgehammer interest-rate strategy and better balance potentially competing objectives of reining in inflation while minimizing strain on and risk of failure of member banks. The Fed agreed to backstop all deposits at both Silicon Valley and Signature Bank and “only” increased the Federal Funds Rate by 0.25% last month, instead of the 0.50% increase that had previously been anticipated. While the Fed has indicated that one more rate increase is likely this year, no one should be counting them chickens before they hatch. As I have said many times, Fed Chair Powell is trying to thread one very challenging needle.

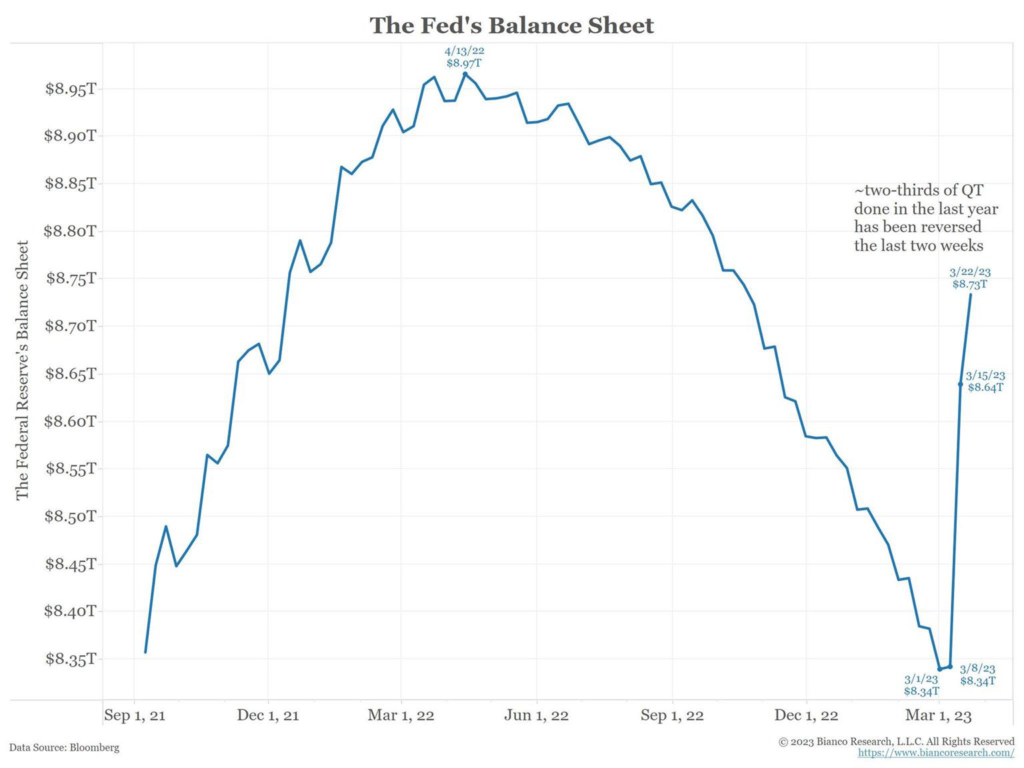

Meanwhile, this aggressive, if not wholly responsible and reasonable Fed response, comes at a cost, of course. The Federal Reserve’s largesse and unprecedented money-printing and quantitative easing endeavors in recent years, which bloated its balance sheet from some $5 trillion (yes, trillion, with a “t”) before the pandemic began, to nearly $9 trillion last April, has been materially responsible for the inflationary pressures we have experienced over the past 18 months or so. Through subsequent monetary tightening efforts, the Fed had successfully shrunk its balance sheet to $8.3 trillion by the beginning of March. And then came the banking shenanigans, the Fed’s response, and in a mere two weeks, some two-thirds of the Fed’s tightening endeavors had been undone. The best laid plans of mice and the Fed, I suppose.

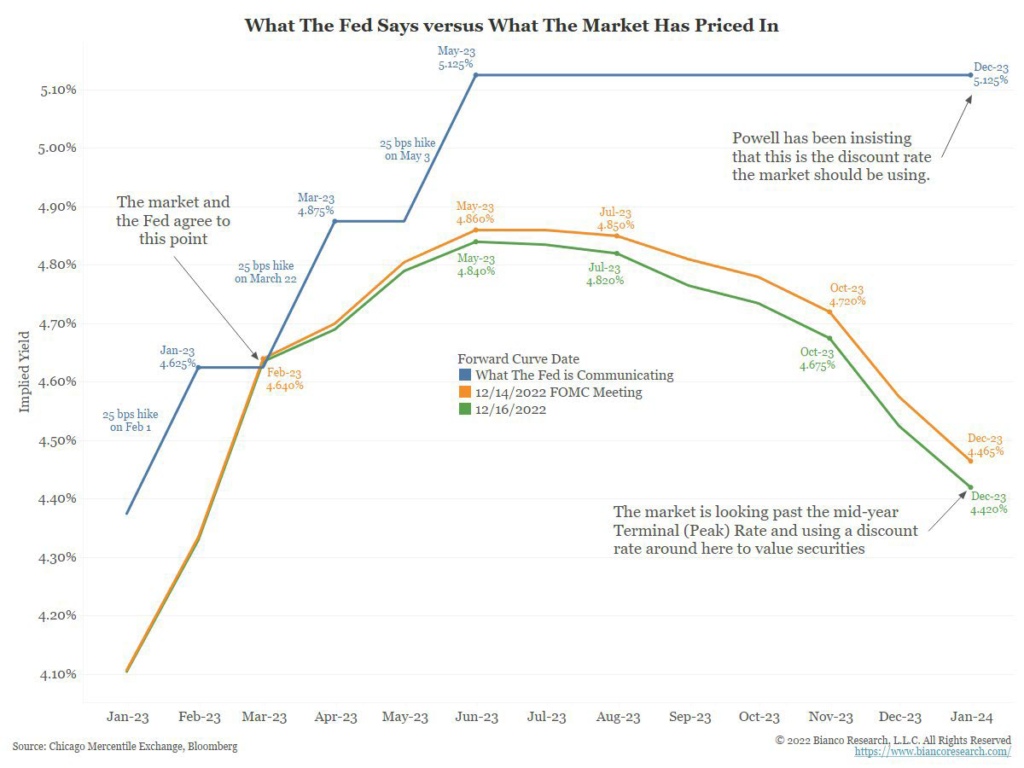

So, where does the Fed go from here? It is hard to say, of course, but there seems to be a disconnect between what the Fed is telegraphing as opposed to what the market is anticipating.

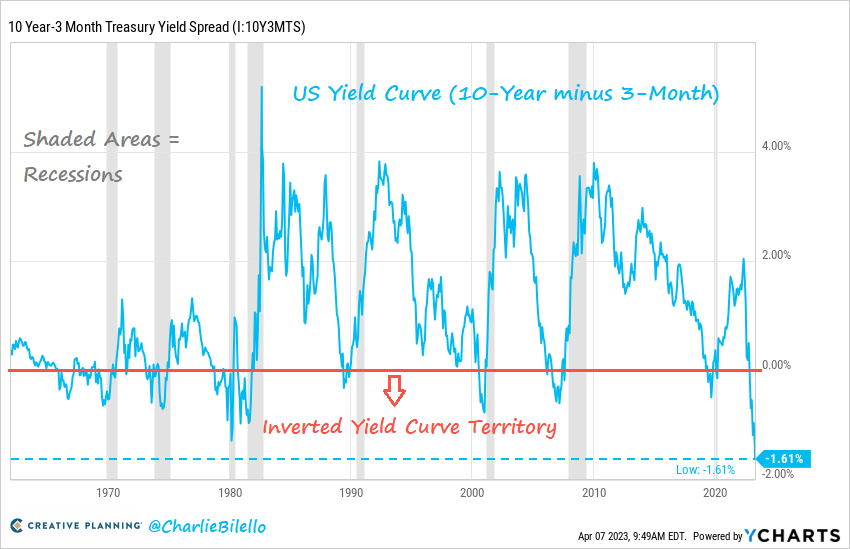

After all, the spread between short- (three-month) and long-term (10-year) Treasuries has never been wider, resulting in the most inverted yield curve in history.

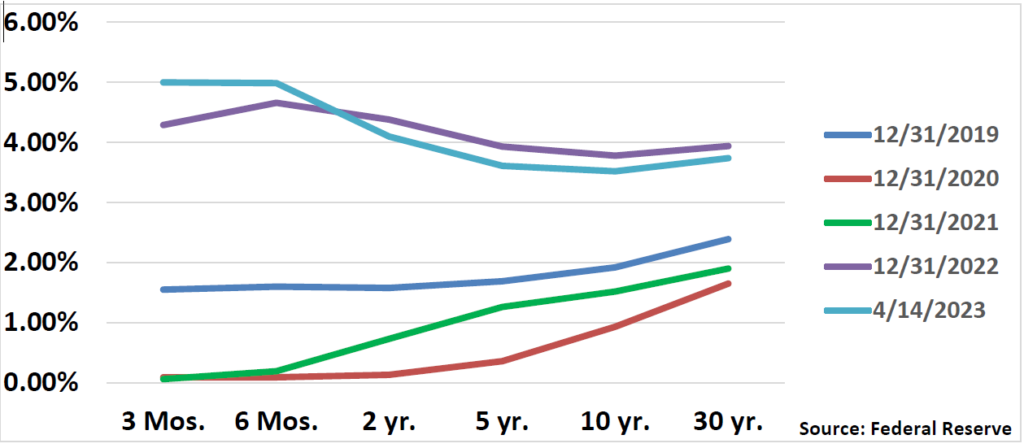

Seen another way, longer-term Treasury rates on two- and ten-year maturities have not changed all that much since the beginning of the year and are actually modestly lower, but rates on the shorter end of the curve have risen. Such a steep inversion would almost certainly foretell a significant economic slowdown, if not recession, but the equity and labor markets (see below) do not seem convinced.

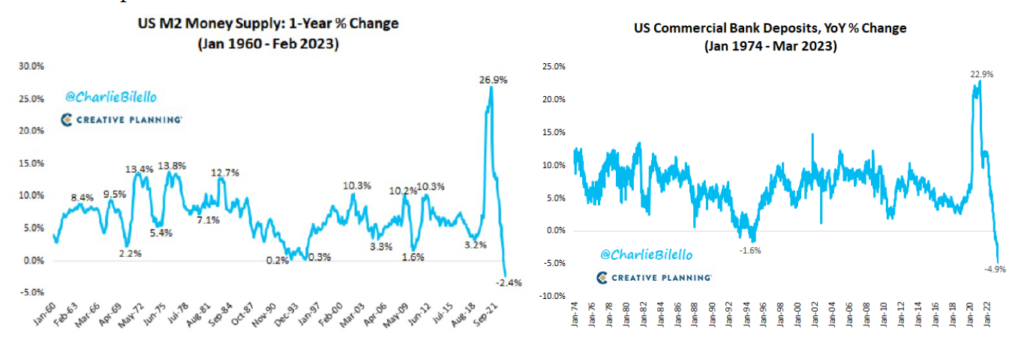

• M2 money supply, in turn, witnessed its largest decline in history during the quarter, as depositors pulled funds from banks in record numbers, preferring risk-free (read: principal-protected) Treasuries and non-bank money market funds versus potentially at-risk bank deposits. It is my strong view that the Fed needs to revisit the anachronistic FDIC-insured limits, which were last changed following the Great Financial Crisis. There is no way that depositors can adequately assess the financial risk of banks in which their deposits are held. That would be asking too much of even this CPA and accounting professor, let alone other depositors, and arguments about moral hazards do not seem very compelling to me, at least when it comes to depositors. Employees, management, Board members, and capital providers (debt holders and stock owners) should individually and collectively bear the risks of bank failures, in my view, not depositors.

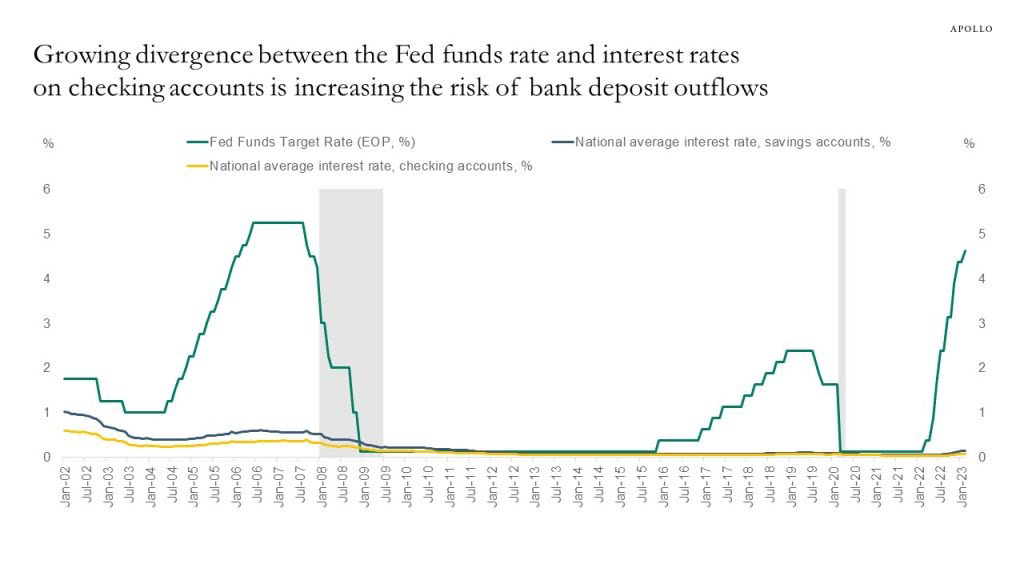

In any case, let’s be clear. The entire banking system remains at risk and subject to whimsical shifts in depositor confidence and psychology, especially given the wide spread between yields on short-term debt securities (think two-year Treasuries) and the Fed Funds rate, both of which approximate 5.0%, and rates banks are willing to pay on many demand deposits, something between jack and squat, keeping in mind that significant balances of these demand deposits are likely uninsured under current rules.

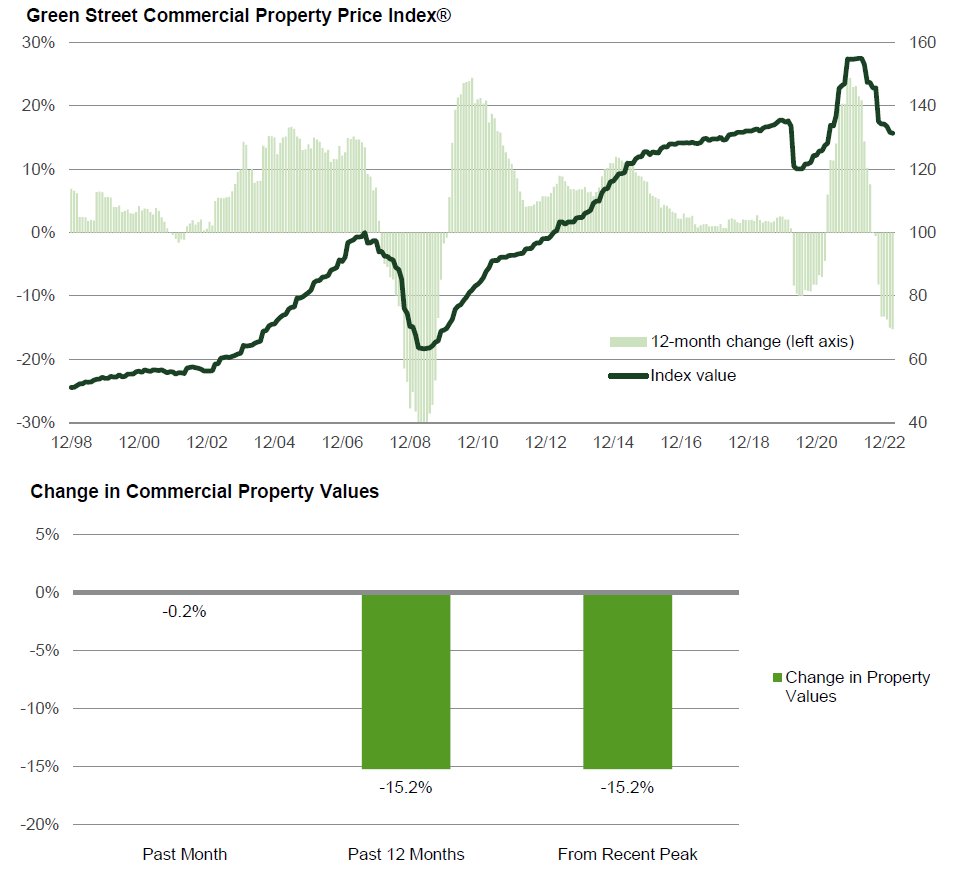

Finally, record levels of commercial mortgages come due this year and next, about $500 billion each year, much of which is held by those smaller regional and community banks, those with less than $250 billion in assets. It remains to be seen how many of those loans are repaid, extended, or ultimately defaulted on, given the significantly higher cost of capital, declines in commercial real estate values, and weakening fundamentals. Maturing commercial real estate loans will provide a worthy adversary to bank balance sheets, especially in the event of increasing delinquencies and/or defaults.

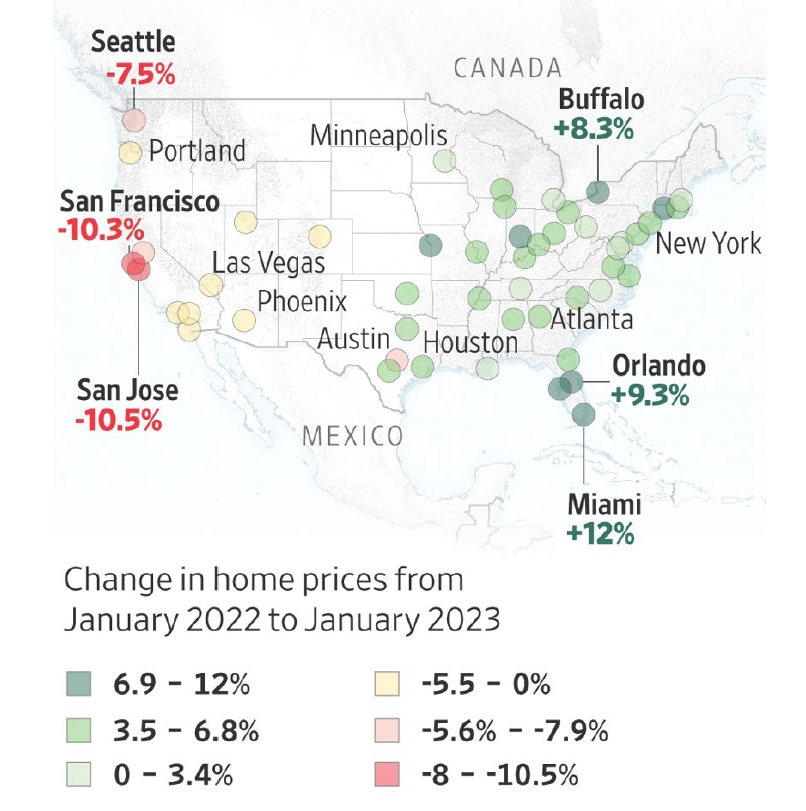

• Housing prices remain firm, though one can argue that it is a tale of different housing markets and different time periods. In all 12 of the major housing markets west of Texas (Austin), home prices declined in January, year-over-year. However, prices actually rose in all markets to the east. Perhaps, it is partly a question of what goes up, must come down (or at least revert to the mean), but the disparity more likely reflects the relative difference in job markets within these geographic locations. Specifically, most of the job losses announced since last year have been in the tech sector, so markets with disproportionate exposure to these industries (e.g., San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles) have been hardest hit.

However, just as in so much other economic data, year-over-year figures often mask nearer-term trends. Since last summer, home prices across the country have dropped for seven straight months (through January). From June’s peak, national housing prices have declined about 5.3%, but are down much more in San Francisco and Seattle, 14.8% and 17.2%, respectively.

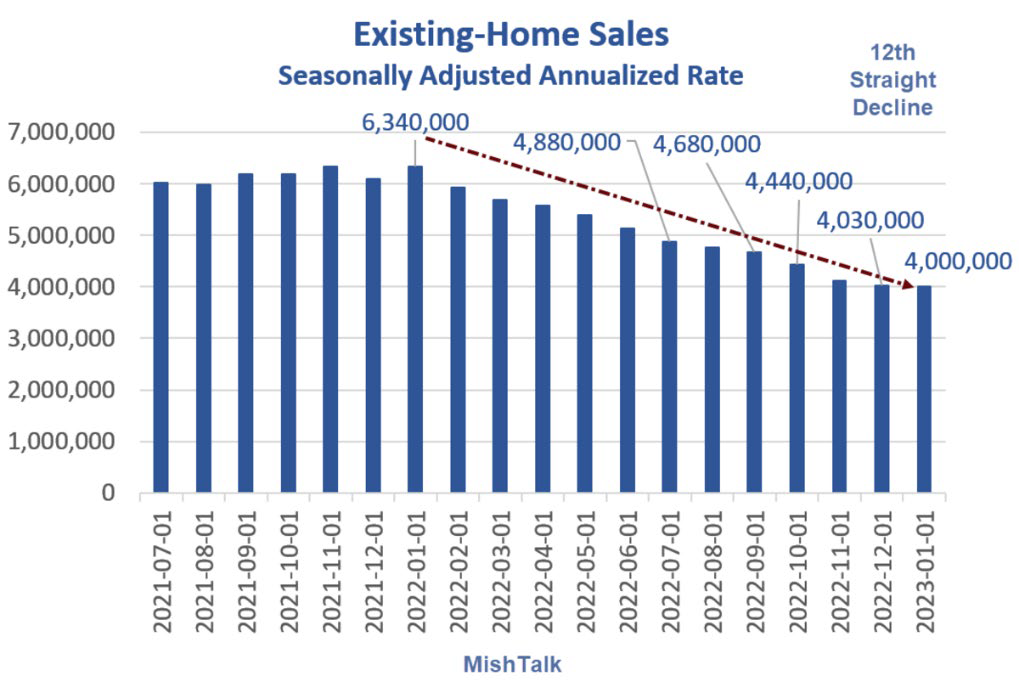

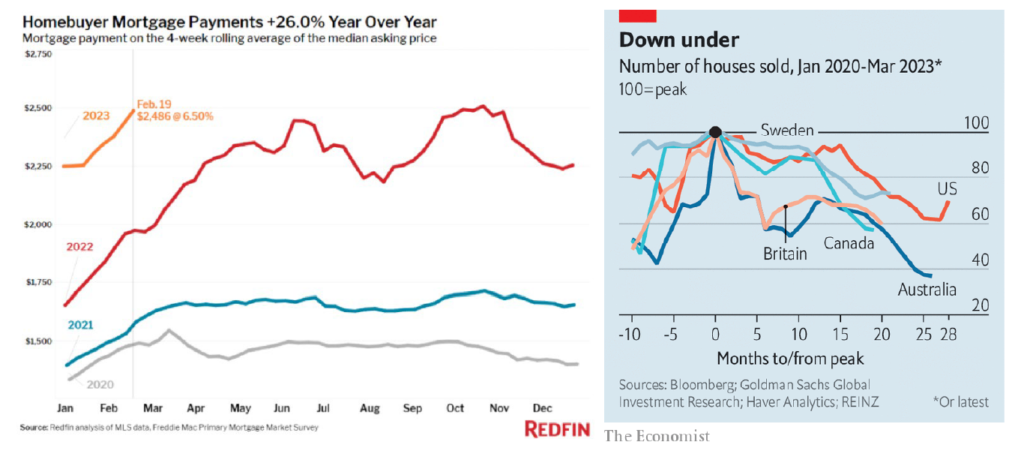

Moreover, all housing pricing data may be a tad skewed because of the sharp drop in transaction volume. Through February, overall home sales are down 22.6% year-over-year, 14.5% from January, and have declined for 12 straight months, whether considering overall or seasonally adjusted data. Higher mortgage rates and declines in consumer (read: homebuyer) confidence are to blame. At last glance, 30-year fixed rate mortgages nationally averaged 6.27%, according to Freddie Mac. While well off the 7.08% rate hit last year, rates are obviously more than double those witnessed in 2021.

In the U.S., the widespread use of long-term, fixed rate mortgages provides a certain buffer to downside risk, as borrowers are able to better able to meet mortgage obligations and are not forced to sell their homes as a result of short-term financial or economic distress. In fact, anyone who acquired or refinanced a home in 2020 or 2021 is now the fortunate owner of “mortgage handcuffs,” (insert joke here), likely unable or reluctant to sell and/or relocate because any subsequent home they might purchase would require substantially mortgage payments (over 25%). The widespread use of fixed-rate mortgages also explains why housing markets in Sweden, Canada, and Australia, where floating-rate mortgages on single-family homes are far more common, have been hit much harder than here in the U.S.

• Meanwhile, data surrounding multifamily markets is decidedly mixed. According to Redfin, asking rents for apartment units fell in every metropolitan area in the U.S. over the last eight months, reflecting not only normal seasonal slowdowns (August through February are traditionally slow leasing periods), but broader indigestion as several markets which saw significant construction activity must “absorb” new units coming to market. Developers of these new projects are engaged in aggressive lease-up efforts, offering generous move-in specials and rent concessions.

According to Redfin, median rent nationally fell 0.4% in March, year-over-year, the first annual decline since March 2020, the start of the pandemic. Rents nationally are down 3.5% since August, with the largest declines in Austin (11%) and Chicago (more than 9%). Other cities with rent declines of 3% or less include Phoenix, Las Vegas, New Orleans, Houston, and Atlanta. However, rents still remain far higher than before the pandemic, up 20 to 35% in many, if not most, markets. And perhaps more importantly, rents in March appear to have rebounded, at least compared to February, up 0.5%, according to Apartment List. Again, year-over-year data can really mask more recent, and arguably, more probative data points.

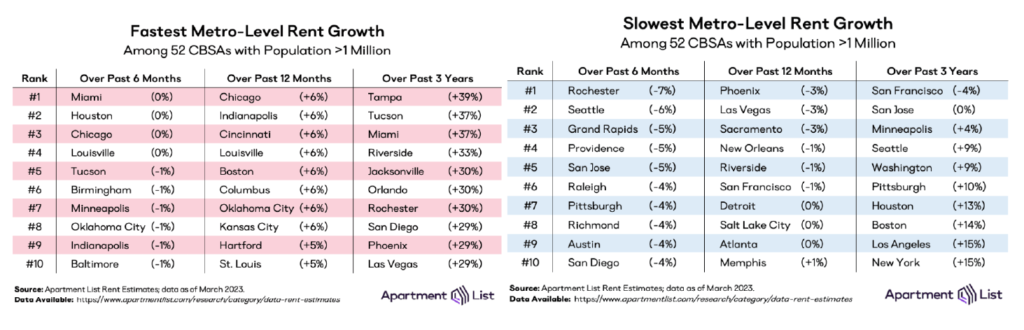

However, while directionally consistent with Redfin, Apartment List’s provides slightly different data regarding specific markets, rental growth (or declines) in said markets, over differing time periods. Anecdotally, those markets with greater exposure to technology and other white-collar jobs (e.g., San Francisco, San Jose, New York, Boston, Los Angeles) and those that experienced the greatest rental growth since the pandemic began (e.g., Austin, Atlanta, Phoenix) are generally those that are experiencing the most modest rental growth, or even experiencing rental declines, at least in recent months.

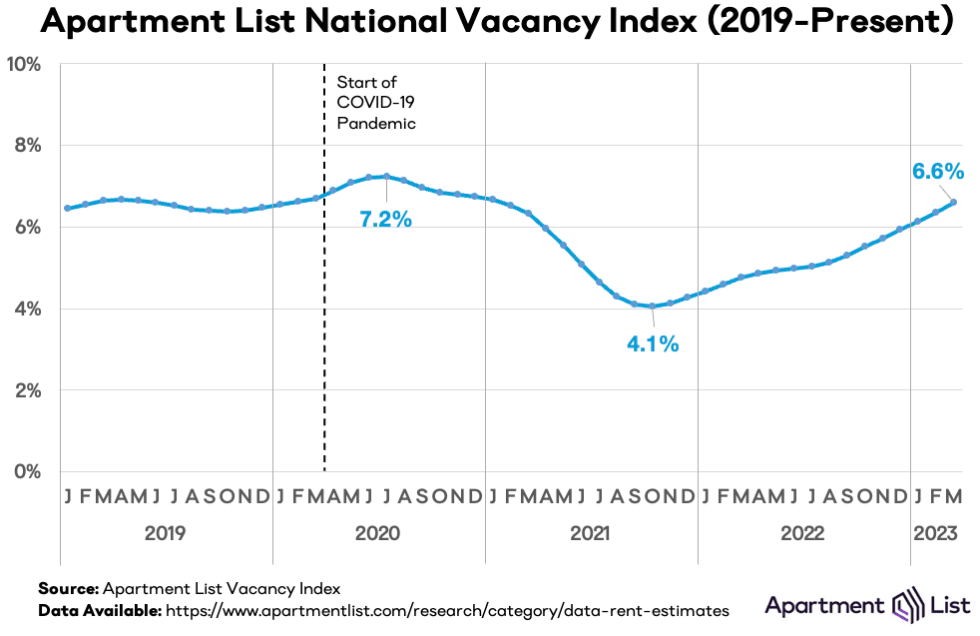

Meanwhile, national vacancy rates ticked up to 6.6%, their highest level since the summer of 2020, again reflecting uninspiring economic growth, higher inflation, and new supply.

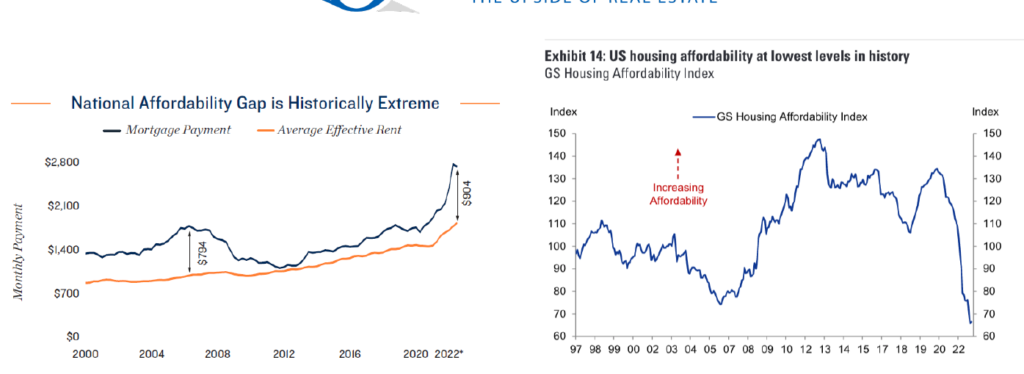

Regardless of shorter-term trends or blips, the “affordability gap,” the difference between mortgage costs and effective apartment rents has never been wider, and homeownership remains decidedly out of reach for most, even two-income, white collar- households. But rising interest rates, higher home prices and decreasing inventory aren’t the only things making it difficult to buy a home these days. Last year, nearly a third of U.S. homes were purchased with cash, according to Redfin, likely foreign and/or institutional buyers. That’s an eight percent increase from 2021, continuing a trend that started during the pandemic, and representing levels not seen since 2014, when the housing market was on the rebound following the Great Financial Crisis. The rise of all-cash purchases comes at a time when the average home buyer is increasingly likely to be white, wealthy, and older, with the proportion of first-time buyers at its lowest in more than 40 years.

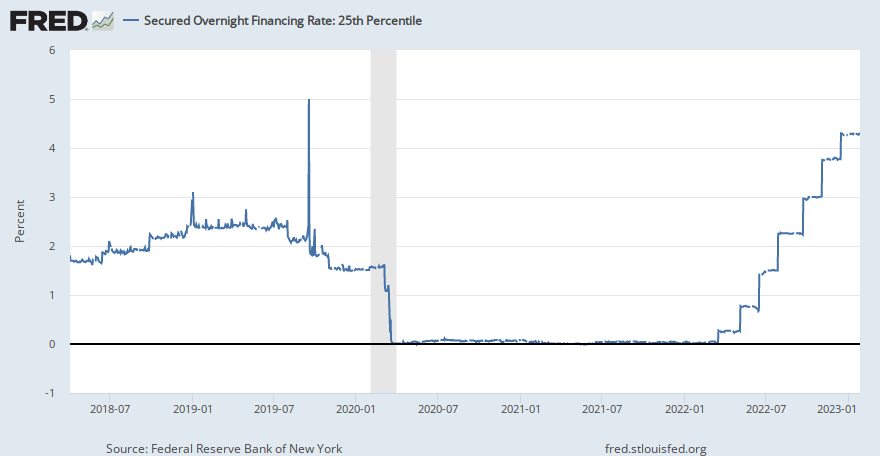

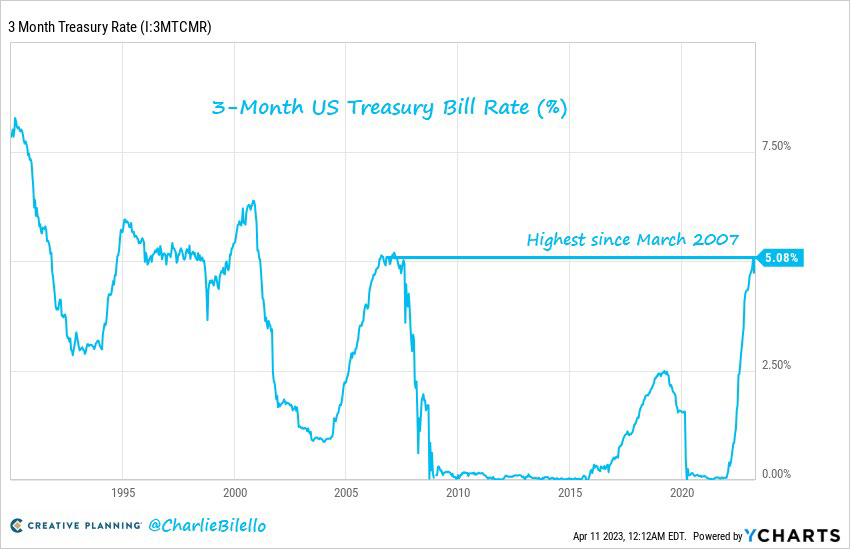

However, higher capital costs and uncertainty surrounding the economy and supply will continue to weigh on apartment valuations and transaction volumes. All property owners, especially those with floating-rate mortgages, are grappling with surges in short-term rates and the increasing costs associated with hedging exposure to such rates (interest rate caps), as yields on both SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) and 3-month Treasuries have spiked to their highest levels on record, or at least since the period preceding the Great Financial Crisis.

The three-month Treasury Bill yield rose to 5.08% this month (5.06% at last glance), its highest level since March 2007. Keep in mind that the yield on short-term Treasuries was 0.70% a year ago, and a measly 0.02% two years ago. Ouch.

Thus, it is no surprise that some apartment owners are struggling. In early April, a large apartment project in Houston, consisting of 3,200 units, was taken back by its lender in early April. Veritas, a San Francisco based PW firm defaulted on a $450 million loan backed by rent-controlled apartments, and Blackstone is currently negotiating with its lenders on portfolio of apartment buildings in NYC.

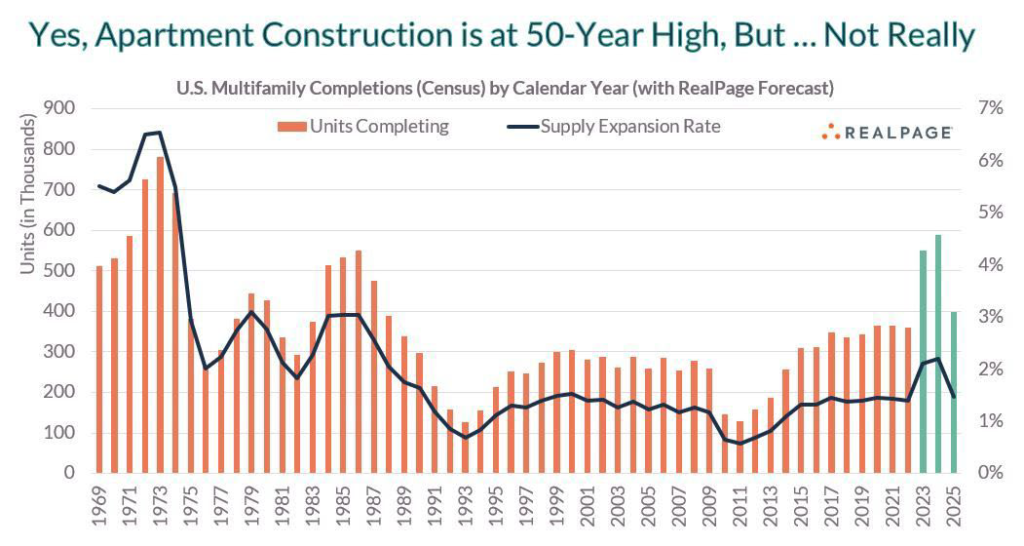

Meanwhile, the multifamily market continues to grapple with increasing supply in several markets. However, while there are about one million multifamily units under construction nationally, one should be cynical when reading headlines claiming that multifamily construction is at its highest level in 50 years, as proclaimed in a recent article published by MHN, Multi-Housing News, since such a claim is inherently misleading or at least incomplete.

For one thing, there are far more multifamily units in the U.S. today than in 1970, so on a relative basis, the increase in absolute construction activity is about a third of what it was in the early 1970’s. Those construction starts in the 1970’s tended to be smaller projects, 20 units or fewer, which were approved and built far more quickly than today. For those of you from Southern California, think about the apartment buildings you routinely see in submarkets like Hollywood, Brentwood, and/or Koreatown. The larger projects which dominate construction starts today take longer to build and bring to market. Finally, the U.S. population has grown significantly since the early 1970’s. For example, there are nearly double the number of adults aged between 25 and 54 today, and those prospective renters or homebuyers reside in different markets than they did back then, reflecting population and demographic shifts, away from both coasts and into markets in the Southwest and Sunbelt, for example.

Now, don’t misunderstand me, as there are a lot of apartments under construction, which along with those higher capital costs and operating expenses (e.g., insurance, labor), are impacting fundamentals and will continue to do so through at least the end of this year, especially in certain markets. However, demand will eventually catch up with supply and with the cost of single-family homes being essentially out of reach for so many, apartments will benefit at least on a relative basis. While the road will be challenging for both developers of new product and operators and owners of existing stock, I believe that the market will stabilize by the end of the first quarter of 2024.

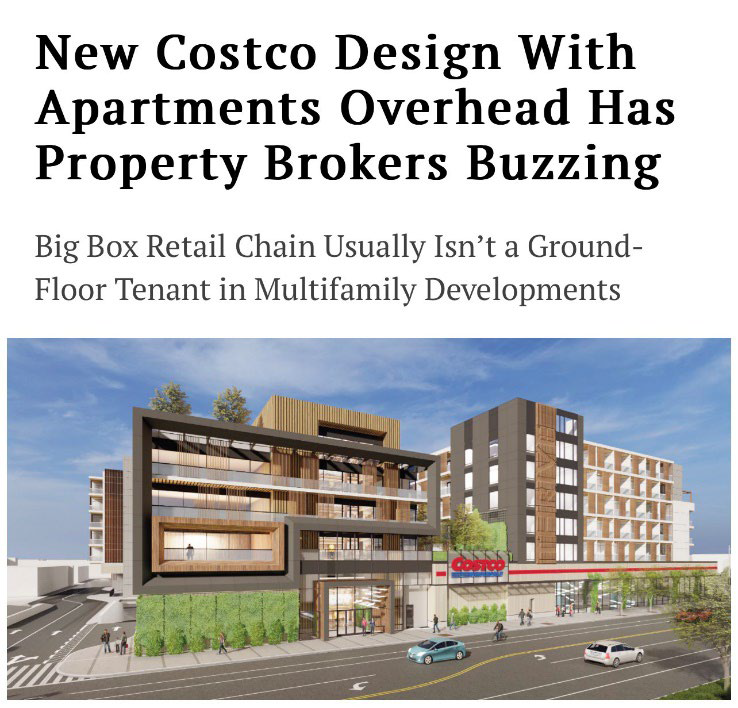

Finally, in what has to be the single most exciting headline in the multifamily space was the news that a local Southern California developer is planning a mixed-use project with apartment units atop a Costco. Imagine, renting an apartment above Costco. You wouldn’t need an on-site gym. Walking the aisles of Costco and lifting cases of drinks and water bottles would provide all the exercise one might need. You could live off of free food samples. If ever one might find heaven on earth, I believe this particular development, if it comes to fruition, would nearly qualify.

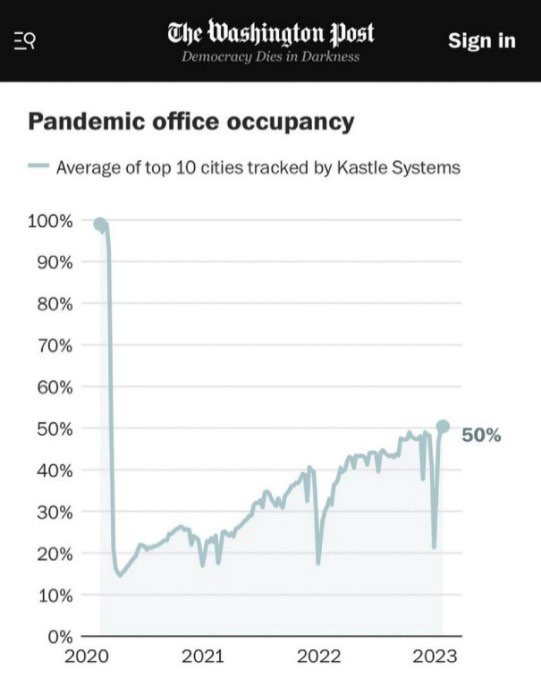

• The commercial real estate market, especially the office sector, saw significant weakness and a large number of foreclosures during the quarter, principally in gateway cities: New York, Los Angeles, Boston, and San Francisco. Few landlords can withstand the double whammy of significant increases in interest rates and weakening fundamentals, which will create additional stresses on operators and lenders in coming quarters. As discussed in greater detail below, to say that the fundamentals in the office sector are not pretty would be a profound understatement. While being a multifamily owner/operator/developer is challenging these days, these challenges pale by comparison to those landlords or operators in the office sector.

This quarter my inbox was flooded with one anecdote or headline after another, each highlighting woes in the office market. Here is just a sample, and trust me, this is (sadly), just a sample:

- “Pac Mutual Building in Downtown LA hits the market at half its previous price”

- “Google Parent Alphabet to spend $500M cutting office space this quarter.”

- “California Government to Trim 132 Office Leases”

- “Distress in Office Market Spreads to High-End Buildings”

- “Blackstone unloads two 13-story buildings in Southern California at a big discount”

- “Brookfield defaults on two Los Angeles office towers”

- “Pimco-Owned Office Landlord Defaults on $1.7 Billion Mortgage”

From Los Angeles to New York to Boston to San Diego to Washington D.C. to nearly everywhere in-between, the office market is in a depression and heavily distressed, experiencing rapidly declining rents, increasing vacancies, and comatose-like transaction volume. Shockingly, there are still a fairly large number of new projects coming to market, nearly 124 million square feet across the country, projects that had already been approved, financed, and begun before the turmoil started, so the beatings will continue for some time.

Billions of square feet of office will probably be obsolete by 2030, reflecting significant overbuilding and a greater shift to hybrid work. Sure, some projects will be repositioned, converted to other uses (e.g., healthcare, medtech, housing), but I remain dubious as to whether obsolete office buildings can be practically converted, and in most cases, I suspect buildings will remain vacant for years, ultimately razed and rebuilt for other uses. Impediments from zoning, architectural/design limitations, lack and cost of available financing for such projects, will simply be too great to overcome.

And retail real estate? It is not faring that much better, though the end of the Covid pandemic is certainly a positive for the sector. During the quarter, I read that Simon Property Group, the largest retail landlord in the country, defaulted on a $295 million loan on a 1.2 million square foot shopping center in Orange County, California, and poor Brookfield, repeating its experience on certain office assets, defaulted on a nearly $80 million shopping center loan in Washington state. There is no question that this will be the most challenging commercial real estate cycle since the 1970’s and I see no proverbial light at the end of the tunnel.

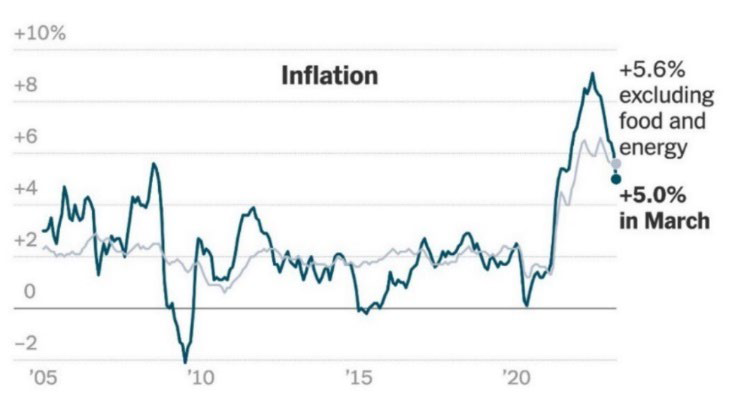

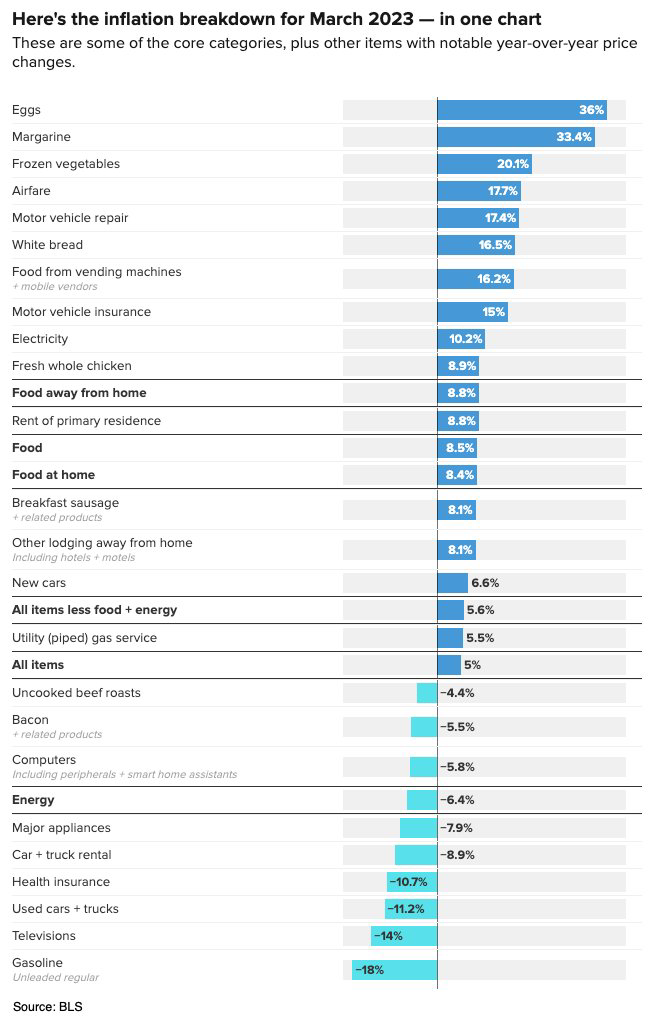

• The Consumer Price Index increased a modest 0.1% in March from the previous month, or 5.0% year-over-year, representing the ninth consecutive decline in year-over-year inflation figures and the lowest inflation levels seen since May 2021. Core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) increased 5.6% year-over-year, driven in large part by continued increases in shelter (housing) costs, which increased 8.2% year-over-year.

With apologies for the size of this next chart, it provides a more granular and insightful breakdown of the yearly inflation change. However, one should exercise caution in drawing conclusions from year-over-year figures because they can obviously mask shorter-term trends that are perhaps more likely to persist going forward. For example, while egg prices rose an astounding 36% between March 2022 and March 2023, they fell 7% in February and another 11% in March. Thank goodness! One can only eat so much oatmeal, Cheerios, and avocado toast, even in California.

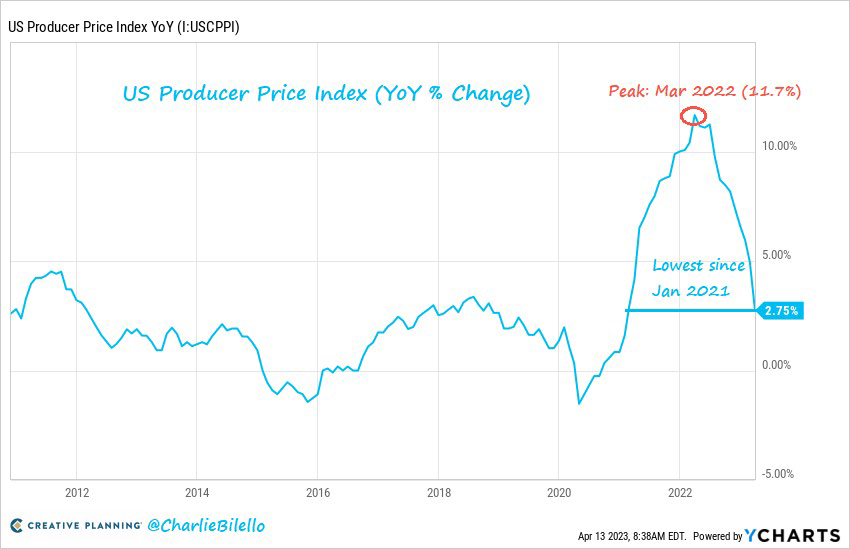

Meanwhile, March 2023 producer prices increased “only” 2.75% over the last year, the smallest increase since January 2021. By comparison, producer prices increased 11.7% in March of 2022 (versus the prior year), so costs have been declining, at least among domestic producers.

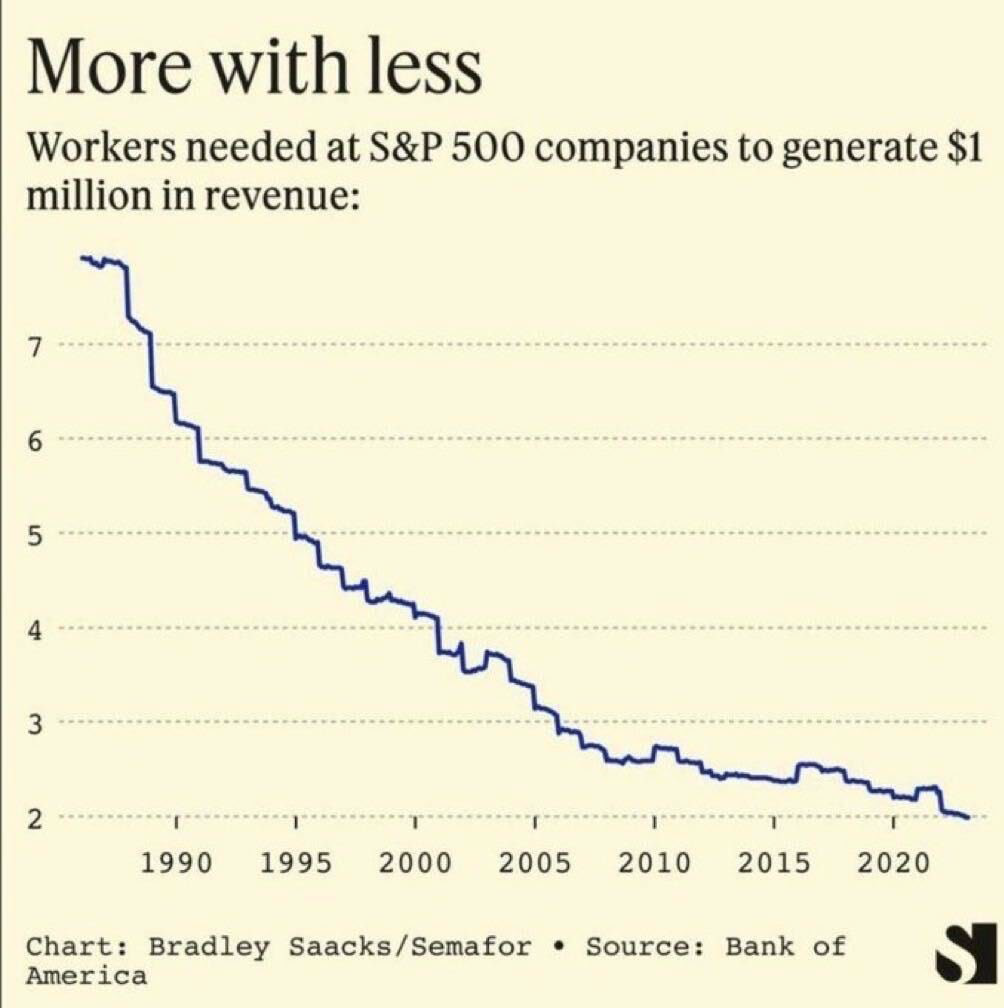

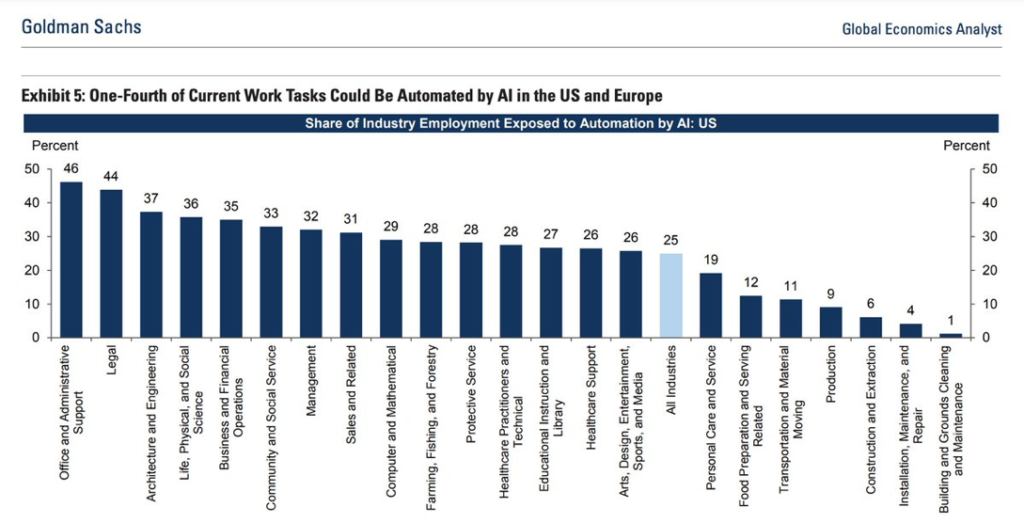

Where inflation goes from here is obviously a big question mark. On the one hand, decreases in housing/shelter costs and in lending activity, coupled with broad demographic and population changes are broadly deflationary. In addition, the continued trend towards automation and yes, AI, should prove deflationary with related changes in labor markets, as evidenced by this interesting graph. Firms require far less workers to generate substantial revenue than in the past.

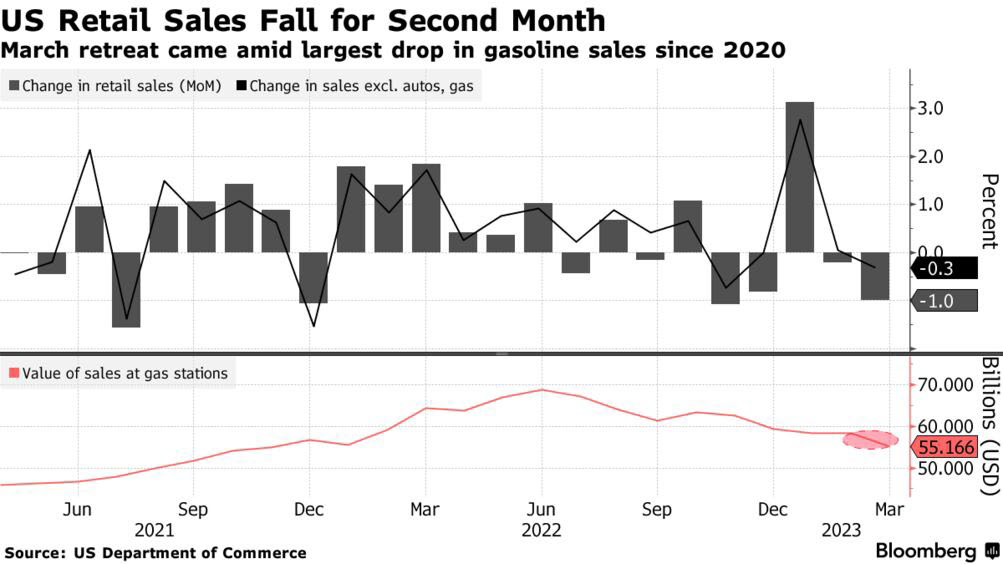

Finally, the consumer seems to be losing some steam, perhaps having finally expended their PPP funds, unemployment benefits, and Covid-related savings when spending dropped like a stone. U.S. retail sales increased only 1.5% in March over the last year, the lowest growth rate since May 2020 and well below the historical average of 4.8%. After adjusting for inflation, the story is worse. Real retail sales fell 3.3% over the last year, the 7th consecutive year-over-year decline.

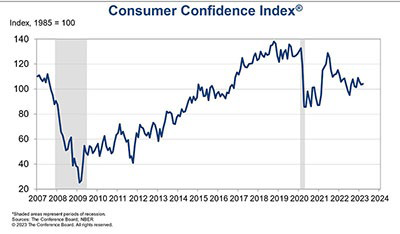

However, data surrounding certain discretionary spending appears contradictory. On the one hand, although I have not been to Las Vegas in recent months in order to obtain data supporting the Sussman Spa Bookings Index (SSBI™), my favorite measure of discretionary spending, I couldn’t help but note that Nevada casinos won nearly $1.24 billion in February, a new record for the month. On the other hand, Darden Restaurants, in a recent earnings call, indicated that households making less than $50K annually were eating less frequently at its Olive Garden and Cheddar’s restaurants according to data, echoing similar comments made by Walmart. Now I realize many reading this memo are not frequent consumers of endless bread sticks at Olive Garden (shame on you), but the anecdotes are consistent with overall trends in retail sales. Recent headlines, especially woes in the banking industry, have understandably weighed on consumer confidence.

In perhaps the scariest data point, “professional economists” (as opposed to the unprofessional or amateur ones) recently surveyed by the Wall Street Journal, project that inflation will slow to 3.1% by end of 2023. My cynicism about such polls is well documented, but if you need any evidence as to how difficult predictions are, not a single one of the economics professionals accurately predicted where interest rates would be at the end of 2022 and not a single number one seed made it to the Final Four in this year’s March Madness. Of course, had my beloved Bruins hoopsters did not sustain the injuries that they experienced and received a number one seed, I am confident we would be hanging up another banner in Westwood. Oh, well. As Andy Dufresne said in the Shawshank Redemption, “Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things.” I have always liked that quote.

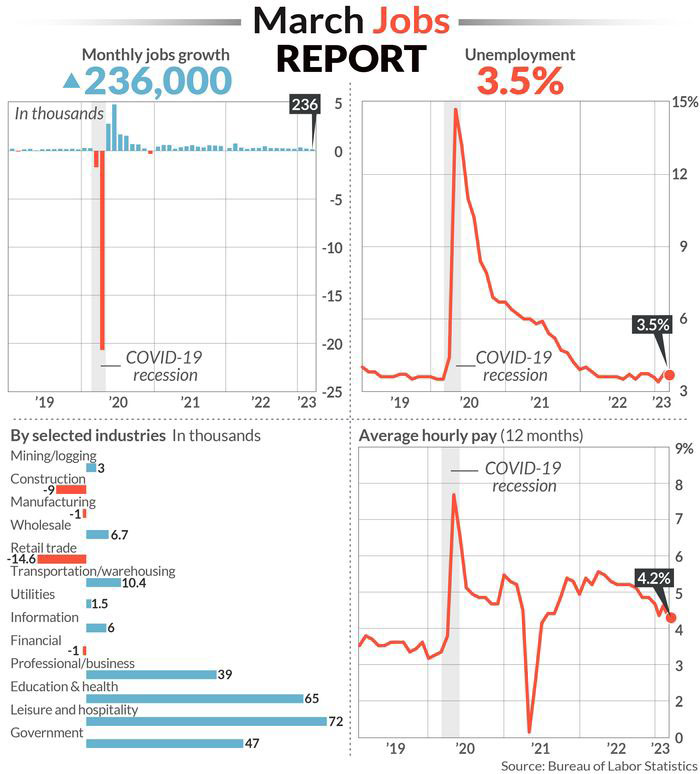

• The job market, while softening, still appears robust, providing a recessionary buffer. The March job report was solid, with an increase of 236,000 new jobs (non-farm) added, slightly exceeding expectations. The unemployment rate fell to 3.5%. Year-over-year average hourly wages increased 4.2%, slightly below the 5.0% inflation rate.

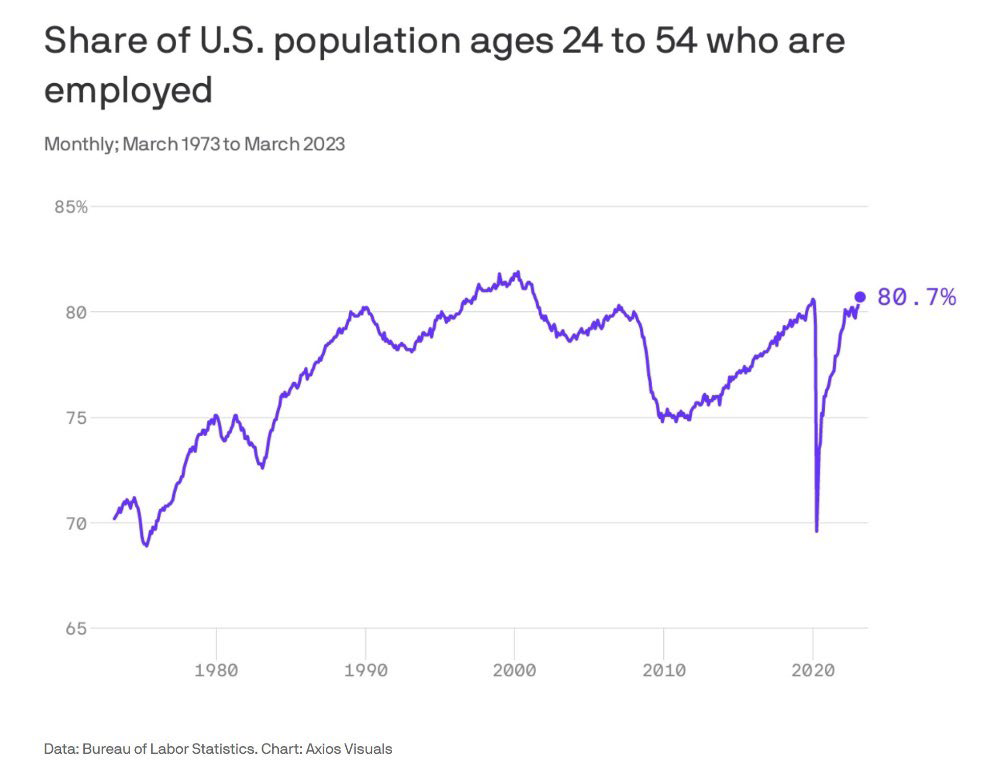

With Baby Boomers (those born after WWII) retiring, we are witnessing labor shortages that many have previously warned about. How do we find more nurses, teachers, bus drivers, and those willing to work in the construction trade (e.g., carpenters, plumbers, electricians)? Who will rebuild the bridges and roads in desperate need of repair, especially when we are already at or near full employment and our immigration policy remains a political football? The share of the U.S. population between 24 and 54 who are employed reached an all-time record in March, approaching 81%, so there is not a heck of a lot of additional labor supply to be found here.

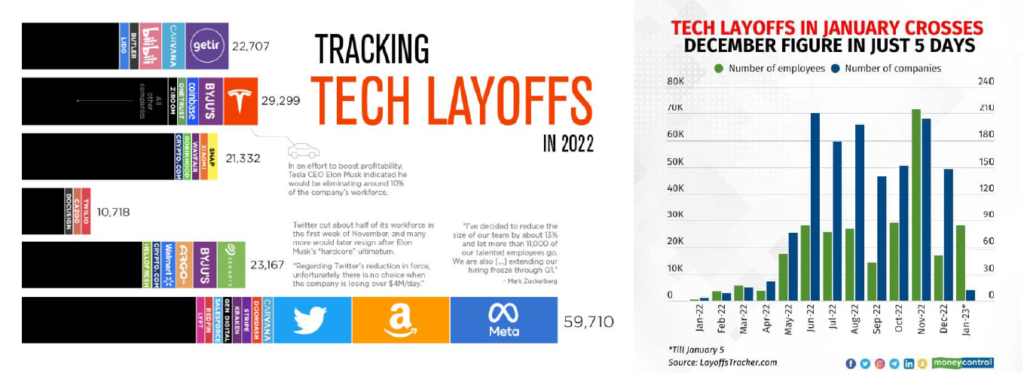

But is not all peaches and cream in the labor markets as layoffs also continue to accelerate, especially in tech, banking, and real estate. Thus far, many laid off workers have been able to find other work, but I am not sure that will remain the case. The running total of layoffs for 2023 based on full months to date is 168,243, according to Layoffs.fyi. Tech layoffs to date this year currently exceed the total number of tech layoffs in 2022, according to their data.

How will AI impact labor markets now and looking forward? This is, perhaps, the most significant uncertainty surrounding employment over the coming years and remains to be seen, of course, but in the meantime, I am relieved that both business school faculty members and managers of financial services firms are not likely to be replaced, at least for a little while.

So, why are so many Americans sour on the economy when labor markets remain reasonably robust, and the stock market continues to hold its own?

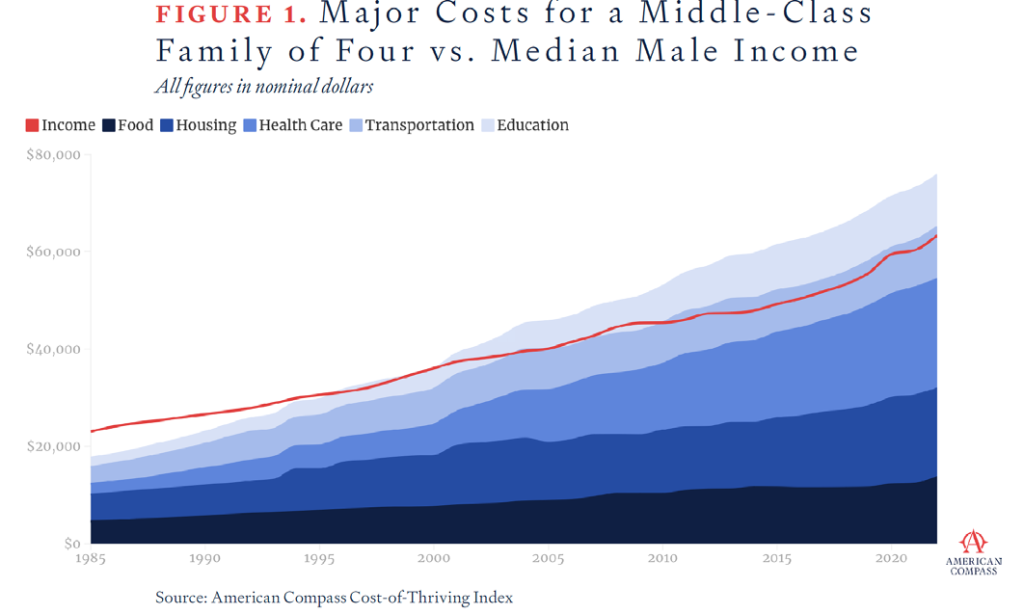

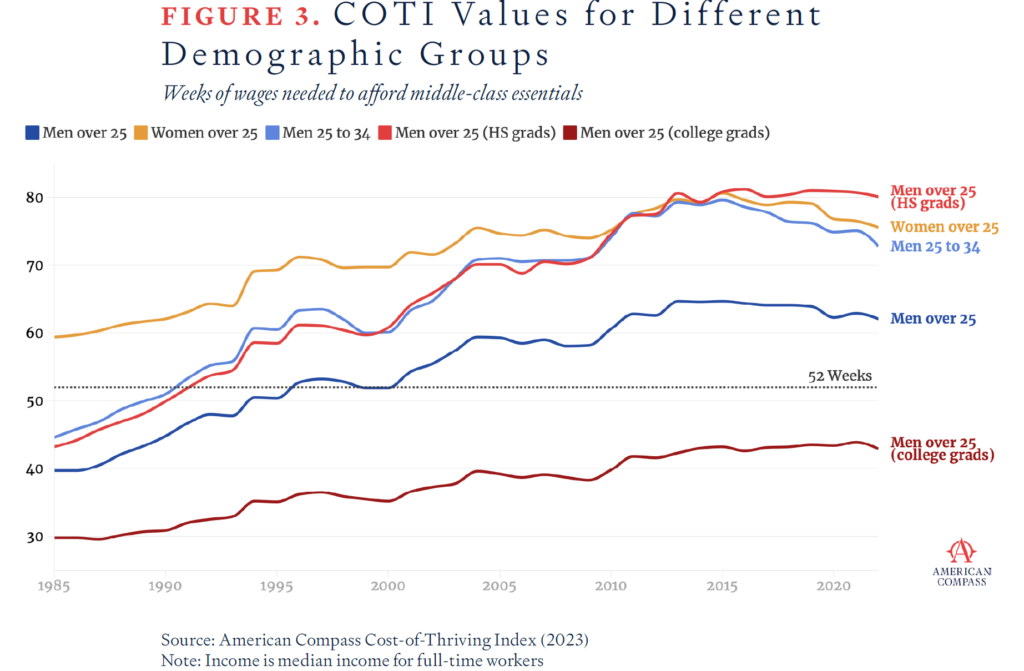

I recently came across some data, released by a conservative think tank (please forgive me, liberal friends), American Compass, and an index it created and labeled, the “Cost of Thriving Index” (COTI) Essentially the index begins with a simple foundational premise, that households must prioritize five sets of goods: food, housing, health care, transportation, and higher education, a sort of modern-day take on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

The COTI strives to measure how the median American family is doing in terms of its ability to afford these goods, by looking at the cost of these five items back in 1985 versus today, comparing them with the median wage someone 25 and older and working full-time would earn, and finally, how many weeks it would take for that wage earner to pay for them. The data and conclusions are sobering, but informative, with two pictures communicating a thousand words.

Here’s the upshot. In 1985, it took about 40 weeks of work per year to pay for these things, giving families room to enjoy other consumer goods and luxuries. And today? It takes more than 62 weeks to afford these same costs. You don’t need to be an expert in the Gregorian calendar to realize the issue. The bottom line is that the median American family simply cannot afford what one would consider life’s necessities on a single middle-class paycheck.

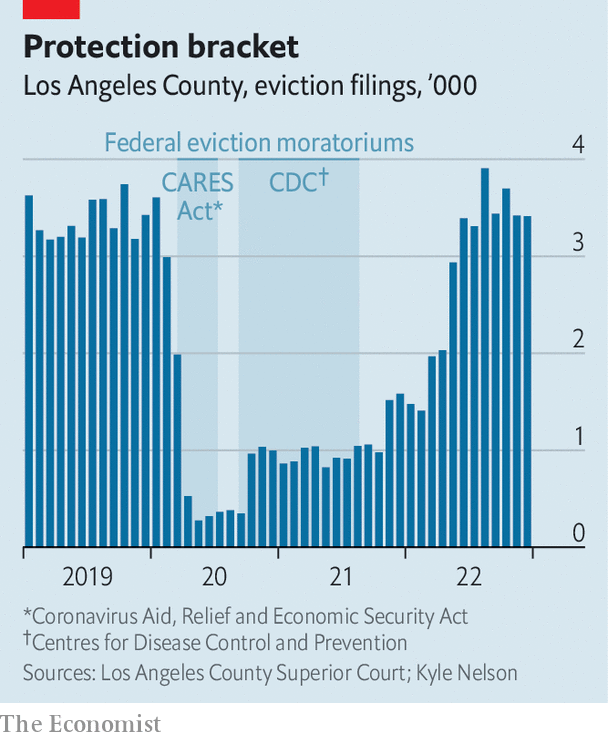

For years, I have written about wealth inequality, the differential between the “haves” and “have-nots” Those with assets – principally, equities, bonds, and real estate – have become richer and richer, creating a wider disparity between themselves and the middle class. So, perhaps the declines in stock prices (since the beginning of 2022), fixed income securities, and more recently, commercial real estate values, along with the substantial job losses in technology, banking, and real estate represent a sort of “richsession” as several publications have described it, a sort of rebalancing, if you will. Blue collar jobs in trades, services, hospitality, and leisure continue to thrive, unions are gaining more traction, and government relief programs, including eviction moratoriums and expansion of rent control (see below), have expanded significantly in recent years, consistent with the thesis.

Either because of, or in spite of, political divisions and broad economic forces (read: wealth inequality), local, state, and our D.C.-based politicians seem eager to promulgate one housing related policy after another, generally benefitting renters at the expense of landlords or property owners

I have predicted for years that the most fundamental premise that “there are more tenants than landlords who vote” and housing has become increasingly unaffordable would result in increased expansion of rent control and inclusionary zoning, along with greater rights afforded tenants facing evictions. According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, 32 states and 73 municipalities have passed new tenant protections, just since January of 2021.

• National “Renters Bill of Rights”: Almost right on cue, President Biden rolled out a proposed ‘Renters Bill of Rights’ in January as a potential push for federal rent control. Not surprisingly, these efforts have been spurred by the Progressive wing of the Democratic caucus, though it remains to be seen whether the push will result in actual legislation or formal policy change. I suspect it is mostly window dressing and no substantive new national policy measures are forthcoming. After all, for certain types of FHA financing, restrictions are already placed on landlords, generally requiring that units be rented only to tenants satisfying certain income tests. And states are, for better or worse, promulgating their own regulations. For example, the Wisconsin and Economic Development Authority and Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency agreed to cap annual rental increases to 5% per year for federal- or state-subsidized affordable housing.

• End of Covid-related eviction moratoriums…or not: One week before they were set to expire, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors extended by two months its tenant protections against eviction for those impacted by COVID-19, while also approving the establishment of a $45 million relief fund for small landlords who have been unable to collect rent from some tenants. At this point, the last phase of Los Angeles’ rent eviction moratorium will end in June 2023. Imagine that. The end of June, months after President declared the national Covid emergency over, and months after every other state had already lifted its eviction restrictions. Understandably, the extension was met with anger from property owners, while The Apartment Association of Greater L.A. (AAGLA) filed a lawsuit against the city to overturn and stop enforcement of the new ordinances that make it more difficult to remove tenants as well as penalize landlords for raising rent.

One ordinance in question stipulates that at least one month’s rent be past due before initiating eviction proceedings. The other forces landlords to pay relocation fees if rent is raised by at least 10 percent or by five percentage points over the rate of inflation, whichever is lower, and results in a tenant’s displacement. That includes paying three times the fair market rent of the unit plus $1,411 in moving costs. Call me a cynic, but I don’t think AAGLA will get much traction in the Los Angeles Superior or local District Courts.

• New York rent regulations upheld by federal appeals court: In New York, rent regulations and restrictions were upheld by federal appeals court, supporting decades old policy impacting about one million apartments. In short, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a challenge by landlords to state law passed in 2019, which made it much more difficult for landlords to free up apartments to achieve “market” rent. As other courts have found, the Second Circuit determined that rent regulations are not an intrusion on property rights or an unconstitutional taking and that legislatures have broad authority to regulate land use without running aground of the Fifth Amendments bar on physical takings. The Court reasoned that landlords are not restricted from receiving market rents “in perpetuity.” In my view, the Courts consistent justification of restrictive rent policies under land-use guidelines is misleading and another example where judicial ends justify economic means. But I call B.S. on this perspective, since it is not the “land use,” which is at issue, but rather the income stream that is derived from that same use. But realizing that judges allow desired outcomes to influence judicial reasoning and rulings is about as shocking as it was to learn that George Santos wasn’t Jewish or an astronaut.

• Rent-related proposals in Colorado, Massachusetts, and Maryland: As indicated above, several states have proposed legislation to protect tenants or ostensibly increase the affordable housing stock. In Colorado, a bill was recently introduced which would give local governments a right of first refusal to purchase multifamily properties before private parties so long as they commit to rent out units for affordable housing. In another measure, which has passed the State House of Representatives, statewide rent control preemptions would be revoked, allowing local communities to establish their own rent-related policies. In Boston, the City Council passed the mayor’s proposal to cap rent at six percent plus the increase in the Consumer Price Index, up to a maximum of 10 percent. However, state lawmakers still need to strike down statewide rent control preemption. Finally, in Maryland, two major counties appear poised to pass rent controls. In Prince George’s County, which surrounds the eastern half of Washington, D.C., county officials just pushed through a measure temporarily capping annual rent increases at three percent. In neighboring Montgomery County, lawmakers are considering two proposals that would cap rent increases at either three or eight percent. Have your popcorn ready.

• Los Angeles’ Measure ULA Tax: The ULA Tax is a new real property transfer tax that was recently approved by voters in Los Angeles. The tax went into effect on April 1st and will be levied in addition to existing city and county documentary transfer taxes. The ULA Tax will be 4% on all real property sales (commercial and residential, whether single- or multifamily) priced between $5 million and $10 million, and 5.5% on real property sales priced or valued at $10 million or greater. You do the math. It’s an extraordinary and very significant tax, which will very consequently impact the industry, reducing property values, transaction volumes, and ultimately, the economics and construction of new housing.

In addition, it's inherently absurd, as it ignores the amount of equity one might have in a home, as it is based solely on the sales price. Therefore, someone selling a $4.5 million piece of property pays no tax, even if the property has no debt, while someone selling a $5 million asset with a $4.5 million mortgage pays the full tax. Finally, while the revenue raised by the new tax is intended to be used to fund affordable housing and tenant assistance programs, I assume it will make nary a dent on homelessness or housing affordability.

And, as always, there are always other interesting economic, financial, and real estate related tidbits that grab my attention

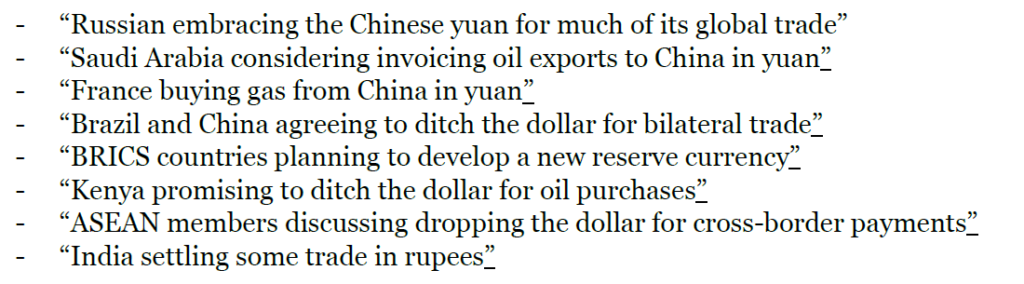

• Rumors of the U.S. dollars demise are greatly exaggerated. Every now and then, a story or three emerges about how this country or that one seeks to diversify away from the U.S. dollar, kicking off frenzied concerns about the inevitable end of dollar dominance. Naturally, these stories provide fertile ground for gold bulls, cryptocurrency promoters, and perhaps just your regular run-of-the-mill grifters to stoke fear about the dollar’s imminent (or just ultimate) death and the potentially catastrophic economic consequences that may follow. Lately, and not surprisingly, perhaps, given the political climate and ability to stoke fear via social media, there have been more than a few such headlines:

Doomsayers offer numerous reasons for the dollar’s inevitable demise, from China’s increasing local and global influence, America’s stagnant economic growth, chronic fiscal deficits, irresponsible monetary expansion and growing debt burden, trade disputes, etc., to challenges posed by potentially disruptive technologies like central bank digital and cryptocurrencies. However, it is my strong view that such rumors are just that, rumors, and that the dollar remains incontrovertibly dominant in global trade and finance, now and looking forward, if not a bit less dominant than before, perhaps Lebron James in the twilight years of his career.

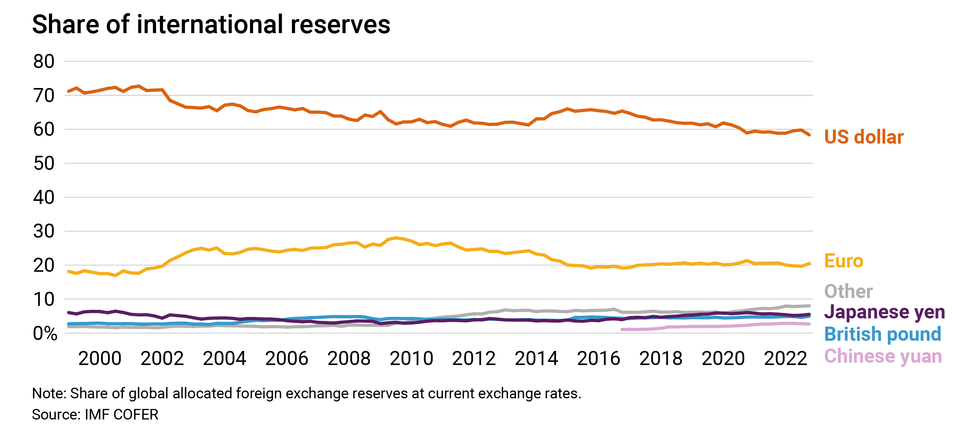

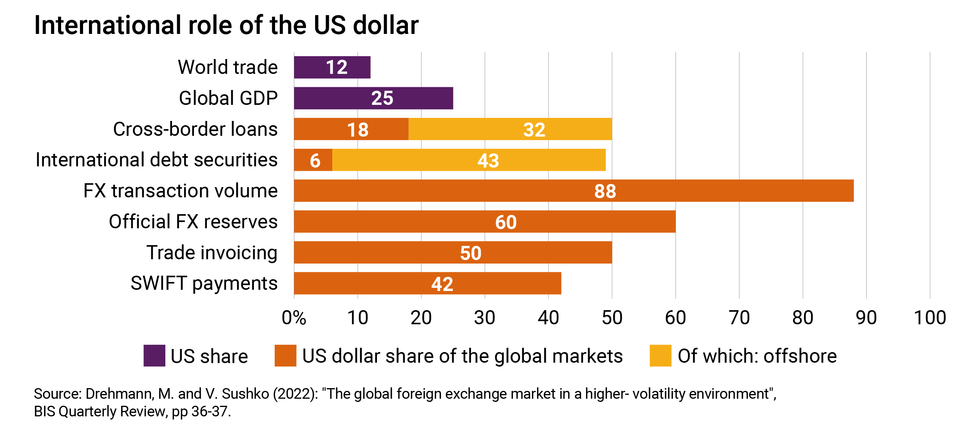

Specifically, while the dollar’s share of central banks’ $12 trillion foreign exchange reserves has declined since 1999, it is still almost twice that of the euro, yen, pound, and yuan combined and the same as it was a decade ago. Its nearest competitor, the euro, accounts for barely 20% of central bank reserves (compared to the dollar’s 58%), followed by the Japanese yen and Chinese yuan at 5% and 3%, respectively.

Moreover, China also employes strict capital controls and foreign investment quotas, as well as a complex system that manages onshore trading and influences offshore yuan activity, so until and unless such controls and heavy-handed management end, I cannot see the yuan replacing the U.S. Dollar anytime soon.

• While the exodus from big cities slowed in 2022, the U.S. population is expected to decline shortly after 2040 if current trends hold: In recent years, I have written extensively about demographic changes and how they might impact real estate markets looking forward. Broadly speaking there have been a few significant shifts in U.S. demographics.

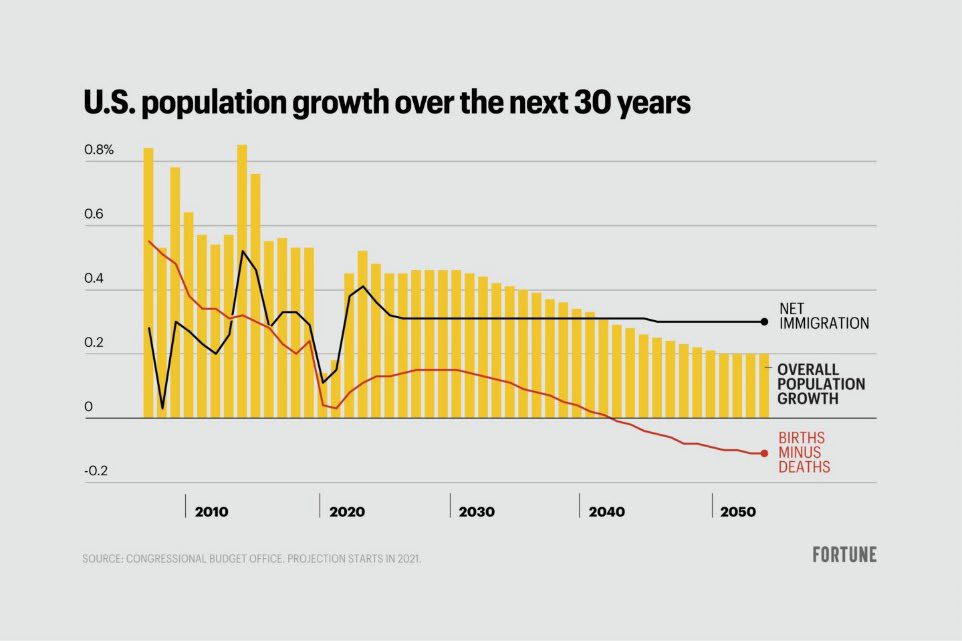

One, folks are getting married later, if at all, and having fewer children. That is a persistent trend throughout the developed world, largely deflationary, and arguably irreversible no matter what incentives might be provided. Let’s face it, feeding, housing, clothing, and educating kids has gotten too darn expensive, especially in populated cities. And without a significant shift in immigration policy, projections indicate that the U.S. population will begin to decline in about 20 years, just like Japan, and more recently, China.

The second was a significant move back to urban cores beginning about 10 to 15 years ago, following decades of “white flight.” However, this trend reversed course again as a result of Covid, when people relocated to less dense suburbs and/or were able to work remotely and moved, if just temporarily. The third has been the relocation of households from the coasts to less expensive inland markets, resulting in the Californication (or NewYorkification) of several cities, from Phoenix to Atlanta, from Reno to Nashville, from Boise to Miami. In fact, California saw some 700,000 residents, net, leave the state following Covid, a figure matched only by New York, which experienced similar population outflows.

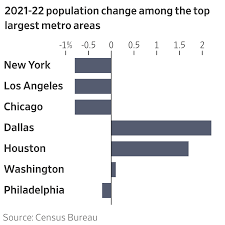

However, recent data suggests that the migratory outflows from the largest metro areas following the pandemic have abated, if not reversed course. However, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington D.C. are still experiencing population declines, though they were far more modest in 2022 versus the 2020 to 2021 timeframe. But with greater remote work options and the obvious externalities of living in urban cores suburbs and exurbs should continue to witness greater relative growth than urban cores. In metro Atlanta, for example, Fulton County, representing the urban core, grew 1.1% last year, while four peripheral counties—Dawson, Jasper, Lamar and Walton—grew at least three times as fast.

In conclusion, the first quarter of 2023 seemed to be the real-world embodiment of this year’s Oscar winner for best picture, Everything Everywhere All at Once, creating additional market and economic uncertainty

Making sense of economic and financial data and forecasting short-term trends is difficult in the most stable of markets, let alone volatile and uncertain markets like those we are experiencing today. The quasi-bank crisis we just witnessed in March merely adds to all the other uncertainties and unknowns we face, from inflation, the related Fed response in terms of the Fed Funds and Quantitative Tightening (or Easing, I suppose), Russia/Ukraine, China/Taiwan, the political environment, and even the impact of ChatGPT and artificial intelligence on just about everything. Perhaps in coming quarters, I will merely ask ChatGPT to write these memos for me. That sure would be a time-saver.

Meanwhile, we are fully aware of the challenges that lie ahead, and we are prepared to address them. For the existing portfolio, that means maximizing occupancy, managing expenses, carefully evaluating capital investment projects, and refinancing debt when possible, especially certain floating-rate debt we have on several of our more recent projects. We know that eliminating distributions, even for just a short while is painful, especially for me and the firm’s principals, given the significant capital we have invested in each and every one of the firm’s projects. But in uncertain times, conservative fiscal management must take precedence. And I remain convinced that the long-term outlook for the multifamily remains bright.

On the other hand, while markets remain challenging, attractive acquisition opportunities await, and we have been fortunate to find several. One is Aspire Seneca, in Victorville, California, a market we know well as we already own two assets in the submarket, including one right across the street. We have also acquired several other assets from this particular seller over the years. The projected returns are higher than we have seen in sometime, and we are still raising capital for that transaction. The other, an attractive three-asset portfolio in the Inland Empire, will be acquired using 1031 funds from two assets we successfully monetized (Aspire Midtown and Aspire Glendale).

With that, the entire Clear Capital team and I pass along our very best wishes to you and yours. We thank you for your continued engagement and support of our firm and its endeavors. And, as always, I want to express a special round of thanks to the Clear Capital Team, who continue to go above and beyond for our clients, colleagues, and partners, especially in challenging times.

Best,

Eric Sussman

Managing Partner